I’m a bit of an oddball. This is not exactly breaking news for most folks who know me. But to paraphrase John Gierach, “If, from time to time, people don’t walk away from you shaking their head… You’re doing something wrong.” I could certainly dedicate an entire article, or even a book, to my oddball qualities, but for this article, I am referring to one specific oddball quality. I fish and guide with a set-up that combines a pack and fly boxes all in one contraption. You’ve seen it. It’s my chest fly box, custom built by the Richardson Chest Fly Box Company in Pennsylvania. It’s awesome and I love it.

I’m a bit of an oddball. This is not exactly breaking news for most folks who know me. But to paraphrase John Gierach, “If, from time to time, people don’t walk away from you shaking their head… You’re doing something wrong.” I could certainly dedicate an entire article, or even a book, to my oddball qualities, but for this article, I am referring to one specific oddball quality. I fish and guide with a set-up that combines a pack and fly boxes all in one contraption. You’ve seen it. It’s my chest fly box, custom built by the Richardson Chest Fly Box Company in Pennsylvania. It’s awesome and I love it.

So, that makes it a little more challenging for me to give advice on individual fly boxes. But I have over the years used about every kind of box and pack known to man. And along the way I have learned a few things that may be helpful to you when purchasing or organizing your flies. At the least, it might get you thinking about it. And who knows? Maybe one day you’ll come to your senses and buy a Richardson!

While chest fly boxes like mine are more common in the Northeast, they are hardly common. Most folks go a different route. They have a variety of different fly boxes that they stuff in a vest, hip pack, chest pack, sling bag, or some other carryall. No matter how you decide to carry them, fly boxes are essential organizational tools in our sport and it helps to know a few things about them.

They come in a number of different sizes, from large, briefcase size boxes for boats to ultra slim boxes not much bigger than a smartphone. When choosing a fly box size, you have to consider how many flies you need to carry, how you’re going to carry them, how big the flies are, and how you want to organize them. For instance, a big, briefcase size box may hold every fly you have but it won’t be very portable when wading creeks. Or a small, ultra slim box might be convenient to slip in a pocket, but if you plan to store bass bugs in it, you’ll only be able to carry a couple and you won’t be able to close the lid.

In addition, you’ll have to consider how you want to organize your flies within your box. There are countless options for securing your flies from slot foam, flat foam, and nubby foam to compartments, clips, and magnets. Some boxes might even have a combination of both, with a type of foam on one side of the box and compartments on the other. Certainly personal preference plays a big role in you box interior of choice, but there are practical matters to consider as well.

Compartments tend to lend themselves well to beefier patterns, or large quantities of the same fly. For instance, if you fish a lot of Pheasant Tails and carry a lot of them with you, it’s far easier to dump them all into one compartment rather than trying to line up three dozen Pheasant Tails across multiple rows of foam. I find foam more useful when I am trying to organize a lot of different patterns but small quantities of each. It’s easier to see what I have.

The type of fly may also determine the best way to store it. Thin foam or magnetic boxes can be great for midges and nymphs but can crush the hackles on many dry flies. On the other hand, trying to carry midges in deep compartments can not only be a waste of space, it can be difficult to grasp them with your fingers when removing them from the box.

Finally, when you’re on the stream, you don’t want to spend your time hunting for flies or digging through your pack for fly boxes. Try to have a designated area of your pack or vest for boxes rather than burying them under a rain jacket somewhere. And if you carry five fly boxes on the stream, try to make them five different, or at least different looking, fly boxes. This will save you all kinds of time when trying to locate a specific box of flies.

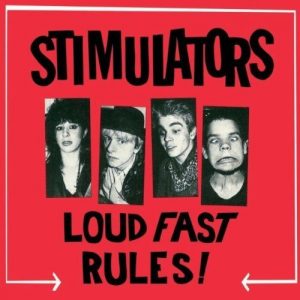

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.