Floating fly lines are by far the most common, and for most trout fishing situations, they are all you need. When nymphing below the surface, weight in the fly or on the leader (split shot) is enough to get the fly and leader down where it needs to be. Doing this while the fly line is still floating can be advantageous as it allows the line to be mended when necessary and provides for quicker pick up when setting the hook on a dead drift. Even when fishing with streamers, a floating line is often adequate when stripping a weighted streamer through shallow trout streams.

Floating fly lines are by far the most common, and for most trout fishing situations, they are all you need. When nymphing below the surface, weight in the fly or on the leader (split shot) is enough to get the fly and leader down where it needs to be. Doing this while the fly line is still floating can be advantageous as it allows the line to be mended when necessary and provides for quicker pick up when setting the hook on a dead drift. Even when fishing with streamers, a floating line is often adequate when stripping a weighted streamer through shallow trout streams.

But what if you want to get a streamer down and keep it down when retrieving it through deeper, swifter water? Such scenarios might include a mountain trout stream that’s running high from recent rain, or a tailwater fishery during generation. Both of these scenarios have produced some of the largest trout I’ve ever caught. Or what if you’re wanting to fish a streamer 12’ deep in a lake for stripers?

Performing the above tasks with a floating fly line would require a very heavy fly with a long leader. And the result would be extremely difficult casting and very limited “contact” with the fly. When fishing streamers, shorter leaders allow you to better control the motion of the fly when retrieving it, and give you much quicker feedback when the fish takes it. Additionally, because of the floating fly line, the fly would rise with every strip of the line rather than staying deep in the target area.

A sink tip fly line solves these problems by allowing the front portion of the fly line to sink. Weightless flies that are easier to cast and sometimes have better “action” can be used and so can shorter leaders. And with the fly line submerged, the fly will stay down and retrieve more in a straight line rather than upward toward the surface. Full sinking lines can also be used for this task but can be clumsy to cast and nearly impossible to mend. A sink tip line more or less gives you the best of both worlds.

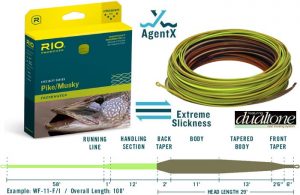

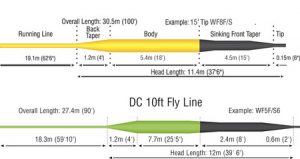

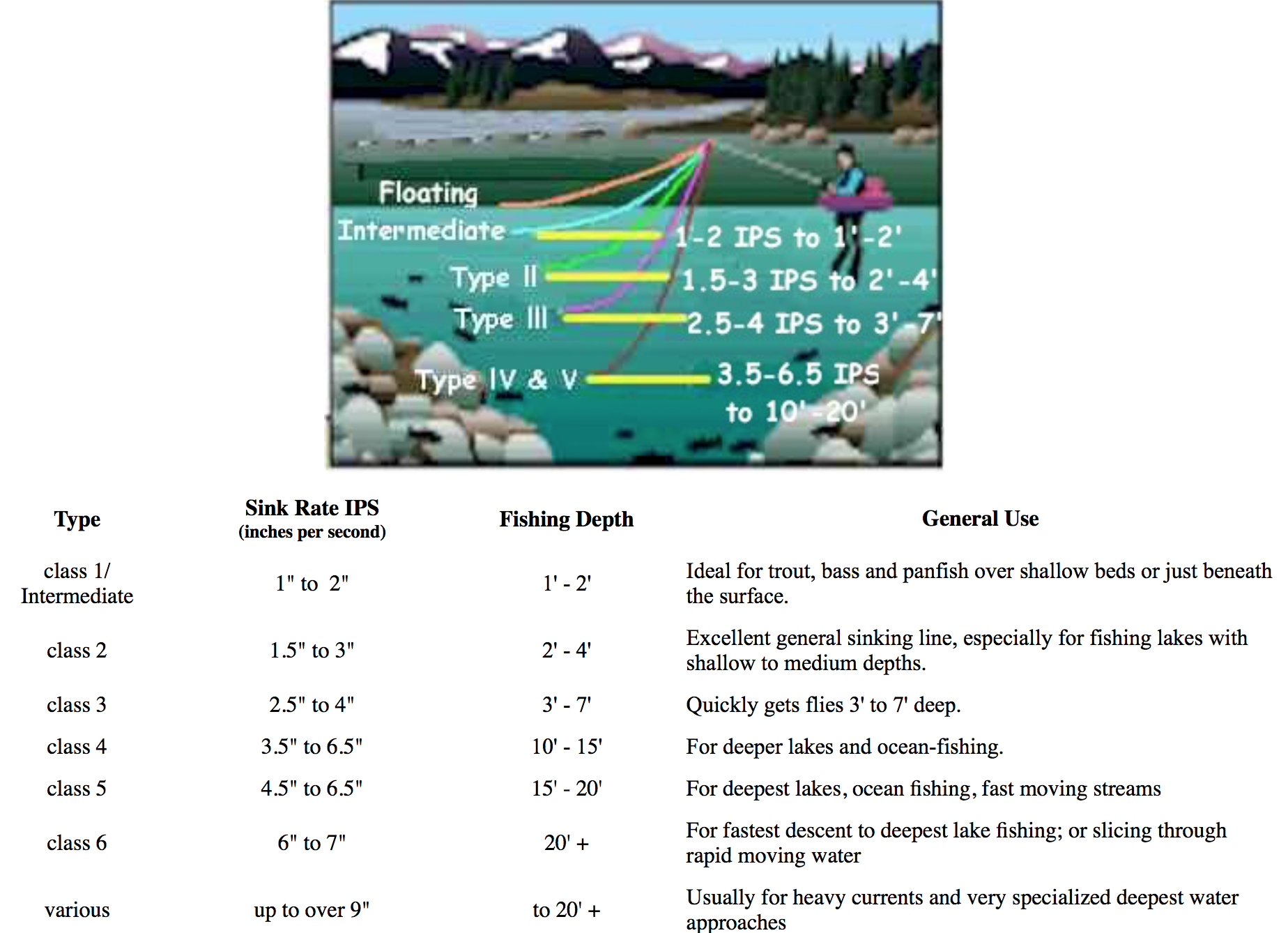

Sink tip fly lines have a number of variations. First, they will often have different lengths of sinking heads. In other words, the entire fly line will float except for the front 6’ or 15’ or whatever the case may be. In general, a shorter head will be easier to cast but a longer head will keep more of the line, and consequently the fly, down deeper. They will also come in different sink rates. Some manufacturers may provide a measurement in grains but most will be designated in a class – like a class 5. A Class 5, for instance, will typically sink at a rate of approximately 5” per second. A Class 2 will sink at approximately 2” per second. They commonly range from Class 1 (often described as an intermediate line) to Class 6.

Very often, the weight classes will correspond specifically with the actual line size. For instance, you may find a 10-weight sink tip line that is a Class 5, or a 6-weight sink tip line that is a Class 3, but there may not be an option for a Class 5 6-weight.

You can also find separate add-on sink tips to convert any floating line into a sink tip. This is convenient if you don’t want to carry an extra spool or if you don’t plan to fish sink tip lines frequently and don’t want the expense of an extra spool and line. However, my experience with these is that they hinge at the connection with the floating line and cast terribly.

You can also find separate add-on sink tips to convert any floating line into a sink tip. This is convenient if you don’t want to carry an extra spool or if you don’t plan to fish sink tip lines frequently and don’t want the expense of an extra spool and line. However, my experience with these is that they hinge at the connection with the floating line and cast terribly.

As with nearly everything in fly fishing, you need to figure out what’s best for your task at hand. Where are you going to be fishing? What are you trying to do? What size rod will you be using?

Hopefully, this sheds a little bit of light on sink tip lines. They can be terribly confusing, mainly because every manufacturer seems to have their own way of describing them. You really need to read through the fine print in the description of the lines to figure out what’s what. Your best bet is to talk to someone at a local fly shop who can really break down the differences for you.

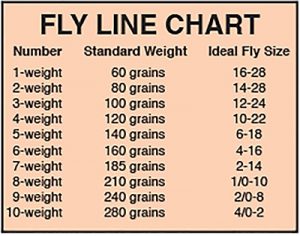

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.