I didn’t know how to break it to him or more importantly, if I even should. He was about to find out anyway, and a few seconds of warning wouldn’t do anything to lessen the unbearable disappointment. From Cecil’s perspective in the front of the canoe, everything was perfect in the world and it was written all over his face. Like a child on Christmas, his eyes were widened to the brink of explosion as he nearly had the last bit of wrapping paper off what was sure to be the gift he’d begged Santa to bring. The sides of his mouth remained cautiously at half-mast but were poised to leap off his face in the anticipated coming moments of pure delight.

He’d been doing everything right, giving the fish line to run on those explosive early sprints and applying side pressure as it made powerful digs in close. Now with his left fingers placed a few feet up the rod, gently pressing the bottom for leverage, the battle was nearly over as the fish was losing steam and beginning to glide upward near the surface. I was in the back of the canoe keeping the craft steady when I got my first good look at this colossal brown, probably twenty-eight inches long and pushing ten pounds, as he made a half-hearted run toward me. Thinking Cecil had weathered the storm, I had a hand on the net and the camera out of the bag when the mighty fish approached in what I expected to be a last second settlement offer before unconditional surrender was demanded.

What I witnessed instead was a final foreshadowing taunt. I’m certain I saw a middle fin extended when a smug grin revealed a #6 Bitch Creek nymph that was no longer firmly embedded in the upper lip of this behemoth. Rather, the fly was carelessly dangling, precariously teetering and struggling for balance, like a top in those last few rotations before collapse.

“The fly’s loose!” I exclaimed as I began to raise the net. “Bring him up now!” The decision had been made. I had to tell him if we were going to have a prayer of landing this fish.

Cecil responded immediately and applied hard steady pressure, raising the fish to the surface. But almost as soon as I had opened my mouth, the fish opened his, and the rubber legs on the detached fly danced as it began its descent to the river bottom. And the brown trout gave me a little wink as his massive shape faded into water.

This wasn’t the first time Cecil had faced disappointment. On a different day at the Cumberland but only a couple of miles downriver, Cecil and I were fishing with Chad, another regular fishing buddy of mine. We were fishing at an enormous gravel bar with a long, broad, powerful, riffled channel running beside it and a vast flat above. We’d anchored the boat above the bar and were spread out wading, Chad at the bottom of the run, Cecil at the top, and me fishing midges to risers in the flat. Despite being a twenty-five degree January day, the fishing had been pretty productive with all of us hooking a few fish in the twelve-inch range. I was in a trance on the flat, trying to keep my eyes focused on the #22 midge pattern, when I experienced déjà vu. “Hoh-lee Shit!” When I heard what is apparently Cecil’s default big fish expletive, I turned to see him once again with rod and arms extended upward, deep bend in the graphite, and reel smoking.

Being a smart ass, I shouted, “You hung up?”

Not amused and surprisingly composed, Cecil replied, “You might want to get down here. I think it’s a good one.”

It didn’t take me long to get there and when I arrived, I found Cecil in yet another epic showdown. The fish, much like his fabled Michigan salmon, had stopped in a shallow beside the riffle about fifty feet from Cecil. He wouldn’t come and he wouldn’t go. He just hunkered down, daring Cecil to make a move. “What’s he doing?” I asked rhetorically.

“He’s not doing anything and I can’t seem to move him.”

“What happens if you go to him?”

“I’m afraid he’ll head back into fast water and break me. I’m fishing 6x. Can you net him?”

“With legitimate concern, I stated matter of factly, “I don’t think he’s ready and I’m not George!”

Chuckling at my reference to a similar pickle encountered in Michigan, he replied, “I don’t know what else to do. Where’s George when you need him?”

Trying to re-focus on the present, I advised, “I’d go to him. Get him on a shorter line where you can control him. If he runs, that’ll give you a chance to tire him out.”

“If he runs, he’ll break me. Can you try to net him?”

“You sure?”

“Yeah. Let’s try it. Worst that could happen is he runs which is what you want me to let him do anyway.”

“Except that you won’t have him on the shorter line,” I reasoned. “You sure you’re sure?”

“Yeah. Let’s see what happens.”

About that time, Chad arrived on the scene and asked what was going on. When I explained that Cecil was tied to an uncooperative pig of a trout and that I was about to try to net him, Chad looked at the fish and asked, “You sure he’s ready?” I responded with a shrug of the shoulders and an uncertain smile that suggested that I was just following orders. When it comes right down to it, the man holding the rod, the man who made this scenario possible in the first place, has to have final say.

So I tried to make my way slowly to the fish. Managing to maintain a stealthy approach, I was nearly within netting range. This just might work! Lord knows Cecil deserves it.

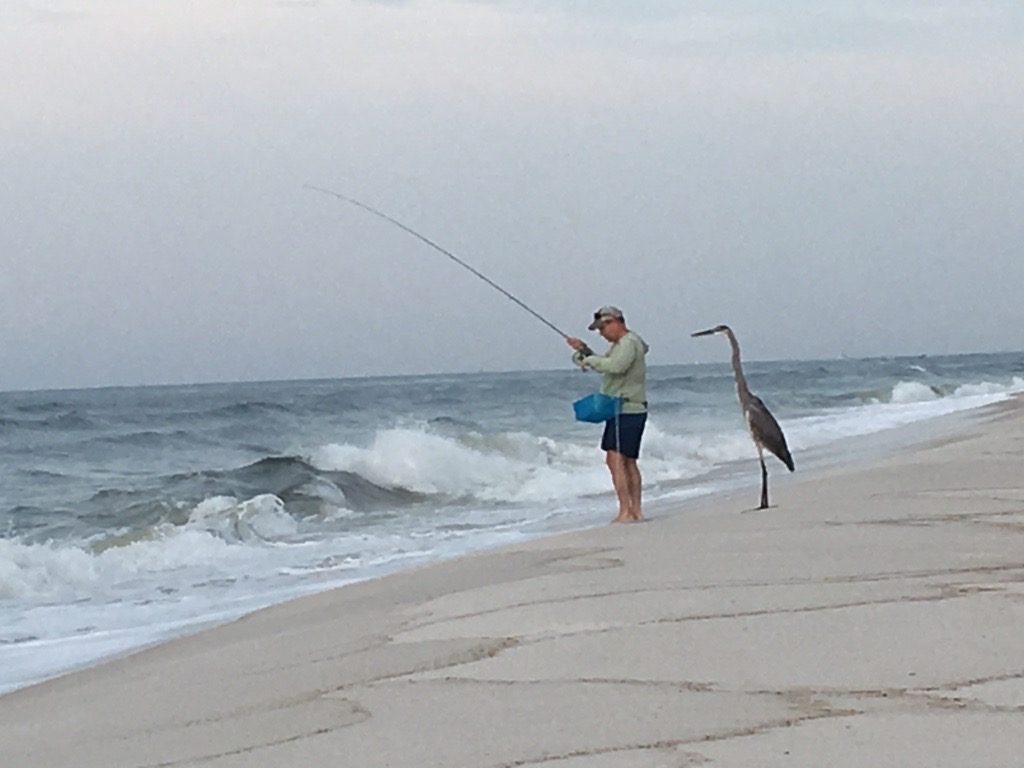

Now within six feet, I had a clear view of the fish and he was every bit as big as the heartbreaker Cecil lost at the canoe. Moving with the caution and deliberate motions of a Great Blue Heron, I slowly began lowering the net as I took another step closer. The fish then began to wiggle in the current, telling me he was about to make his move. I knew it was now or never, and just as I began to make a desperate lunge with the net, I could clearly see the trout’s face. He gave me the exact same look that Michael Jordan gives a defender before blowing by him to the basket. And that’s exactly what he did. Easily side-stepping the net lunge, he proceeded with shocking speed, a crossover dribble, a spin move, and dunked right over Cecil. Line limp. Cecil dejected. Crowd silent. Bulls win.

Though disappointed, Cecil took it all with good humor and even posed with Chad for a grip-and-grin photo with arms outstretched, holding an invisible fish. The curse would continue for years to come as he would have epic battles with epic fish on every large river and tiny stream that you can imagine. It’s hard to feel too sorry for him, though. While often coming up short, Cecil has hooked and played more giant fish than many anglers could ever hope to even see. As Tennyson so eloquently put it, “Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.”

Cecil is cursed. At least he was. Like the Chicago Cubs in baseball, Cecil spent many years on the water where he just couldn’t seem to catch a break. Oh, he caught plenty of fish, and some pretty nice ones at that. He’s a very good fisherman, after all. But being a cursed fisherman does not make you a bad fisherman. It was those fish-of-a-lifetime catches that haunted Cecil. If there was a big fish in a run, and I mean a really big fish, Cecil would find it, hook it, play it, and then manage to lose it in the most heartbreaking way possible. Well, except for that salmon on the Pere Marquette in Michigan. But he had some help on that one.

At that time, my lifelong friend Mike was working for Anheuser-Busch and living in Michigan. Mike really wasn’t a fly fisherman but he was anxious to try, so Cecil and I met him in Michigan for a few days of fishing and camping. Trout would be fine, but we were really hoping to catch the fall run of salmon from Lake Michigan. On our way in, we stopped at Johnson’s Lodge to get the skinny from my buddy Sean, who informed us that we had more or less missed the run on the Pere Marquette but that the salmon were running well on the Manistee. And we didn’t question this at all. Religious salmon and steelhead fisherman know. They stay on top of and in pursuit of these runs like surfers follow big waves.

Road weary and eager to fish, we opted to set up camp on the Pere Marquette, maybe do a little trout fishing, and then head to the Manistee in the next day or two. It didn’t take us long to set up camp and we still had a few hours of daylight left, so we headed down to the river in hopes of catching an evening hatch. Expecting to cast dry flies to trout, I had my Winston four-weight, Cecil took a soft, five-weight Sage Light Line series, and Mike took whatever-the-hell we had left over. The first pool we came to was right above a small island where the river split around in two narrow channels. Cecil decided to fish there while I took Mike to a long run upstream where I could help him with his casting.

Mike was getting the hang of things pretty well, and I was about to leave him alone and head upriver when we heard that all too familiar expletive fly from the pool below. “Hoh-Lee Shit!” When we looked downriver, we saw Cecil with his rod bent over double and line screaming off his reel. With no attempt to disguise the urgency of the situation, he shouted over the zinging reel, “Rob, get your ass down here!” Mike and I reeled in as quickly as we could and plowed our way down the brushy bank.

By the time we got there, his reel had gone silent and the pool was still, but his rod was still bent deep into the butt. “You hung up?” I inquired legitimately this time.

Staring intently at where his line met the water and seemingly annoyed at my question, he replied sharply, “Hell no, I’m not hung up. I think I’ve got a salmon!” I followed his line about forty feet to the water and noticed the silver reflection at the other end – not budging an inch.

“I’ll be damned, I think you’re right,” I said with excitement. “What’s he doing?”

“He’s not doing anything. He quit running and I don’t have enough rod to move him.”

Trying to help, Mike advised, “Why don’t you go to him?”

“I tried that but every time I take a step toward him, he tries to run. I’m afraid he’s going to run me into that fast water beside the island, and there’s no way I could keep him on. Rob, do you think you can go behind him and net him?”

Removing my narrow, terribly undersized, eighteen inch Brodin net from its magnetic connection on the back of my vest, I looked over at the monster of a fish, back at my net, back at the fish, then at Cecil. “I’ll try.” As I tried to make my way around the back of the pool for a sneak attack on the fish, we noticed two guys coming from the back of the island – guys that had been in the woods for a while. They looked like they might live on the island. Stopping right next to where Cecil’s fish was firmly anchored, they looked down at the fish and up at Cecil.

“Purty nice fish ya got there,” one stated in a twang that hardly suggested Michigan origin.

“Thanks,” Cecil replied politely but obviously annoyed at the distraction.

Again looking down at the fish and back at Cecil, the potentially manifesto-writing-backwoodsman flatly stated, “You ain’t got enough rod.”

“No shit,” Cecil replied with a smile. “I was fishing for trout. My buddy’s comin’ around to help me with the net.”

Now shifting his attention to me and my pitifully inadequate net, he obviously came to the same conclusion I did earlier. I just didn’t want to disappoint Cecil. “That net? Ain’t no way. You want George here to hep you land eem?”

Seeing nothing in their hands or on the bank, I inquired, “Do you all have a bigger net?”

“Nah. George don’t needa net. He does this all the time. He loves it.”

Now having flashbacks to Larry, Darryl, and Darryl on the Bob Newhart Show, I wondered if George was able to talk. But I needed to focus. We were in a crisis here.

Knowing this wasn’t my call to make, I looked to the man with the fish for guidance. “Cecil?”

“Well somebody do somethin’. I can’t move the son-of-a-bitch.”

Taking charge, I looked over at the good ol’ boys on the bank and gave the order. “Go get ‘em George!” None of us had any idea what would come of this. I guess in the back of my mind I was expecting George to be the fish whisperer. He would ease his way toward the fish, gently coo and stroke it, and then delicately lift it from the river with no protest at all from the salmon.

Instead, like Hulk Hogan from the top rope, George dove from the island on top of Cecil’s fish. Mike and I were in tears – Cecil was in shock. Not really knowing protocol for this situation, Cecil pointed his rod tip toward the water, figuring George might want some slack. Good thing too because George was really into it with the fish, the two rolling violently in the water like Tarzan wrestling a crocodile. It didn’t last long though. In a matter of seconds, George had the fish out of the water, and in one continuous motion, body-slammed him on the island. Though, if I’m being completely honest, I think it technically may have been an Atomic Drop.

George emerged wiping the fight off his hands and displaying a proud, every-other-tooth grin and I suspected he had done this before. Proud of his friend in a Dr. Frankenstein and his monster kind of way, George’s interpreter boasted, “I told you boys George’d get em.”

“He sure as hell did,” I chimed in.

Realizing the salmon would soon die anyway, from natural causes as much as George’s Atomic Drop; Cecil made the offer to the backwoods dynamic duo, asking, “You want him?”

“You sure?” replied the interpreter.

“Yeah,” Cecil said lying. “We’ve already got a mess of trout back at camp.”

“Sure, we’ll take it. ‘Preciate it. The boys down at the VFW will love it.”

“No problem,” Cecil assured him. “Can I just get my picture taken with him real quick?”

So, deep in the archives, you can find it – a grainy photo from a disposable camera, yellowed out from age. Standing on a small island in the Pere Marquette River, Cecil is holding his delicate five-weight rod, with the smile of someone floating high above ground, and George is displaying his scatter-toothed smile through a beard that hadn’t been trimmed (or cleaned) in probably fifteen years. Between them they are holding a mighty twenty pound salmon, covered in grass, mud, and scratches. And if you look at the photo closely enough, you can kind of tell where the fish has a black eye.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

Last month, I talked about ways to simplify your fly selection and offered tips on how to choose flies based on season and what was hatching. Based on the number of questions I had, however, I left out an important part of the process. Many folks said they are often uncertain when to fish a dry fly vs. a nymph.

Last month, I talked about ways to simplify your fly selection and offered tips on how to choose flies based on season and what was hatching. Based on the number of questions I had, however, I left out an important part of the process. Many folks said they are often uncertain when to fish a dry fly vs. a nymph. If you are new to fly fishing, particularly for trout, it is easy to be overwhelmed by the number of fly patterns available. Which ones do I need? What colors? What sizes? Do I need all of them? First of all, if you tried to carry every trout fly with you, you’d need a wheelbarrow to go fly fishing! While there is no way to make it immediately simple, there are ways to simplify the process. As with many things in fly fishing, you try to find a good starting point and learn as you go from there.

If you are new to fly fishing, particularly for trout, it is easy to be overwhelmed by the number of fly patterns available. Which ones do I need? What colors? What sizes? Do I need all of them? First of all, if you tried to carry every trout fly with you, you’d need a wheelbarrow to go fly fishing! While there is no way to make it immediately simple, there are ways to simplify the process. As with many things in fly fishing, you try to find a good starting point and learn as you go from there.

Every time I go to the beach on vacation, I take a fly rod with me. Sometimes I already have plans to do some flats fishing with a guide but just as often, my only plan is to get up early each morning and cast around in the surf to see what might bite. That’s one of the neat things about fishing in the ocean. You never know just what you might find!

Every time I go to the beach on vacation, I take a fly rod with me. Sometimes I already have plans to do some flats fishing with a guide but just as often, my only plan is to get up early each morning and cast around in the surf to see what might bite. That’s one of the neat things about fishing in the ocean. You never know just what you might find!

These are hardly the idealized fly fishing journeys that most anglers conjure in their minds in those last few moments before sleep takes hold. It’s not the casual, early morning stroll through a dewy meadow to the spacious pool in a lazily meandering river where 20-inch trout routinely clock in for their daily shift of methodically sipping delicate mayflies. In fact, unless you are one of a few passionate, dedicated, and perhaps slightly mentally unbalanced backcountry anglers, you might consider these journeys way too much like work.

These are hardly the idealized fly fishing journeys that most anglers conjure in their minds in those last few moments before sleep takes hold. It’s not the casual, early morning stroll through a dewy meadow to the spacious pool in a lazily meandering river where 20-inch trout routinely clock in for their daily shift of methodically sipping delicate mayflies. In fact, unless you are one of a few passionate, dedicated, and perhaps slightly mentally unbalanced backcountry anglers, you might consider these journeys way too much like work.