When it comes to fishing dry flies in the Smokies, particularly on the smaller streams, I am typically looking for two primary things in a pattern: It needs to be visible and it needs to be buoyant. Beyond that I can begin focusing on a few more details like color and size.

In general, trout in the Smokies don’t see heavy hatches of individual insects. Rather, they mostly see small quantities of a lot of different insects. So, if you can present the fly naturally and without spooking fish, most any all-purpose, “prospecting” fly pattern will do the trick. As mentioned above, if you can get a little more precise with size and color, your pattern will be that much more effective.

Matching size will require more observation of bugs on the water or simply having general knowledge of what should be hatching. The same two things can help with matching color but also having broad knowledge of how seasons impact color can put you ahead of the curve. With some exceptions, aquatic insects tend to blend in with their surroundings. So, in winter months when trees are bare, most of what hatches is dark. As foliage comes in, most of what hatches is brighter.

The Stimulator has long been a favorite fly pattern of Smoky Mountain anglers for all of the reasons mentioned above. Its buoyancy and light colored wing not only make it easy to see, but make it a perfect “indicator fly” when fishing a dropper. And if you mix and match sizes and colors, you could nearly fish a Stimulator 12 months out of the year!

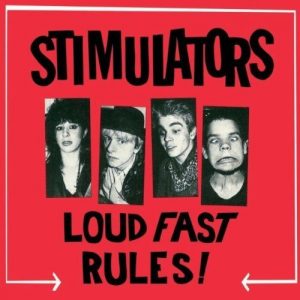

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

In any case, the fly seems to have been created to imitate an adult stonefly, but it is also a good suggestion of a caddis and sometimes even a hopper. I most often fish it in yellow and in sizes #16 – 8. I think the smaller size makes a great imitation for the prolific Little Yellow Sally Stoneflies, and the larger sizes are good representations of the larger golden stones that hatch on summer evenings in the mountains. In the fall, I often fish a #10 Stimulator in orange to imitate the large ginger caddis.

Whether it is imitating anything or not, it catches fish and it floats well in heavier pocket water found throughout the mountains. It is one of the most popular dry flies ever invented for trout and can be found in most every fly shop in the country.

Yellow Stimulator

Hook: Daiichi 1270 #16 – #10

Thread: 8/0 orange

Tail: Stacked elk hair

Abdomen: Yellow floss

Abdomen Hackle: Brown rooster neck – palmered

Wing: Stacked elk hair

Thorax: Bright orange dubbing

Thorax Hackle: Grizzly rooster neck – palmered

Learn more about Southern Appalachian fly patterns and hatches in my Hatch Guide.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.