For those with more of a spin fishing or bait fishing background, you may be used to casting a weighted lure or live bait with sinkers. You have a reel of monofilament line and when you cast, you propel the weighted lure forward and it carries all of the monofilament line with it.

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.

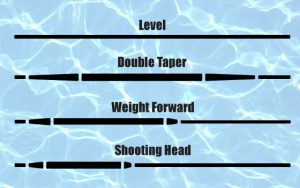

Most fly lines will have a core of come sort and a plastic coating. Saltwater lines usually have a more rigid monofilament core, while freshwater lines usually have a softer, suppler Dacron core. When the plastic coating is applied, it is usually done in such a way to achieve a particular taper. The taper is how and where the weight is placed on the line and how it is designed to behave.

A weight forward taper is the most common. If the fly line is 90’ long, which is typical, the first 50’ or so that attaches to the backing and the reel will be thinner and level. Approximately the front 40’ of line will be thicker except for the last few feet where it attaches to the leader. The intention is for the weight to be in the front part of your line to maximize casting efficiency at your most common distances. For longer casts, the thicker, weighted portion “pulls” the thinner, un-weighted portion behind it with a technique called shooting line.

There are variations on this weight forward design for specialty situations. For instance, a bass line may have a shorter but more dramatic taper, where more weight is placed in a smaller area. The purpose of this is to aide in turning over the heavier, more wind resistant flies commonly used in bass fishing. Some of these variations are referred to as ‘shooting heads.”

A double taper line is becoming less and less popular but is one I still really like for fishing smaller streams like in the Smokies. It has a more gradual taper and it tapers equally from the middle of the line out to each end. This design allows for more delicate, accurate presentations at distances of 40’ and closer, and it roll casts extremely well. It’s also nice because you when you wear out one end of the line, you can turn it around and use the other. It is a disadvantage for distance casting because when you get beyond 40’, you get into the “reverse taper.”

You may also run across level lines, especially at discount type stores. There is no taper to level lines. They can be attractive to the beginner because they are so inexpensive but they cast horribly. Unless you are getting into some specialty techniques, I would avoid level lines altogether.

Most fly lines float. Even when fishing weighted flies in streams, a floating line is most often used because the fly and leader can usually sink enough to get the fly where it needs to be. However, there are sink tip lines available in different weights, where the front part of the fly line will sink to get a fly down deeper and faster. These are more commonly used for streamer fishing in lakes or deep, swift rivers. Full sinking lines are also available but not used very frequently. They allow the entire line to sink but are extremely difficult to cast.

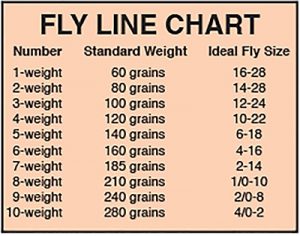

Fly lines are sized by a line weight that is designated by a single number like a 4-weight or 9-weight. This is intended to match the same designation on a fly rod, so you would use a 5-weight line on a 5-weight rod. It takes the amount of weight in a 5-weight line to properly flex or “load” a 5-weight rod and make it cast its best. If you used a 2-weight line on a 5-weight rod, there wouldn’t be enough weight to load it and you’d throw your arm out trying to get the line out. If you used an 8-weight line on a 5-weight rod, it would overload it, resulting in a hard, clunky cast that was hard to control. There may be some specialized situations where you may want to over-line or under-line a rod, but 99% of the time, you want to match the line weight to the rod.

You choose what line weight (and rod weight) you need based on what you’re fishing for. For trout, you’re typically casting smaller flies to fish in clear water and trying to achieve delicate presentations. Lighter lines in the 3 to 5-weight range are common. For largemouth bass, you’re probably fishing more stained water and commonly casting bigger, more wind resistant flies. You’ll be able to better accomplish this with 7 to 9-weight lines/rods. In saltwater, you probably want heavier lines not only for heavier flies, but also to contend with heavier winds.