Floating fly lines are by far the most common, and for most trout fishing situations, they are all you need. When nymphing below the surface, weight in the fly or on the leader (split shot) is enough to get the fly and leader down where it needs to be. Doing this while the fly line is still floating can be advantageous as it allows the line to be mended when necessary and provides for quicker pick up when setting the hook on a dead drift. Even when fishing with streamers, a floating line is often adequate when stripping a weighted streamer through shallow trout streams.

Floating fly lines are by far the most common, and for most trout fishing situations, they are all you need. When nymphing below the surface, weight in the fly or on the leader (split shot) is enough to get the fly and leader down where it needs to be. Doing this while the fly line is still floating can be advantageous as it allows the line to be mended when necessary and provides for quicker pick up when setting the hook on a dead drift. Even when fishing with streamers, a floating line is often adequate when stripping a weighted streamer through shallow trout streams.

But what if you want to get a streamer down and keep it down when retrieving it through deeper, swifter water? Such scenarios might include a mountain trout stream that’s running high from recent rain, or a tailwater fishery during generation. Both of these scenarios have produced some of the largest trout I’ve ever caught. Or what if you’re wanting to fish a streamer 12’ deep in a lake for stripers?

Performing the above tasks with a floating fly line would require a very heavy fly with a long leader. And the result would be extremely difficult casting and very limited “contact” with the fly. When fishing streamers, shorter leaders allow you to better control the motion of the fly when retrieving it, and give you much quicker feedback when the fish takes it. Additionally, because of the floating fly line, the fly would rise with every strip of the line rather than staying deep in the target area.

A sink tip fly line solves these problems by allowing the front portion of the fly line to sink. Weightless flies that are easier to cast and sometimes have better “action” can be used and so can shorter leaders. And with the fly line submerged, the fly will stay down and retrieve more in a straight line rather than upward toward the surface. Full sinking lines can also be used for this task but can be clumsy to cast and nearly impossible to mend. A sink tip line more or less gives you the best of both worlds.

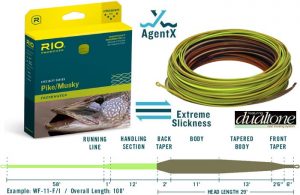

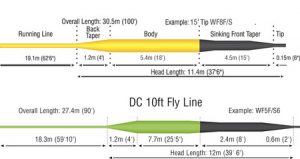

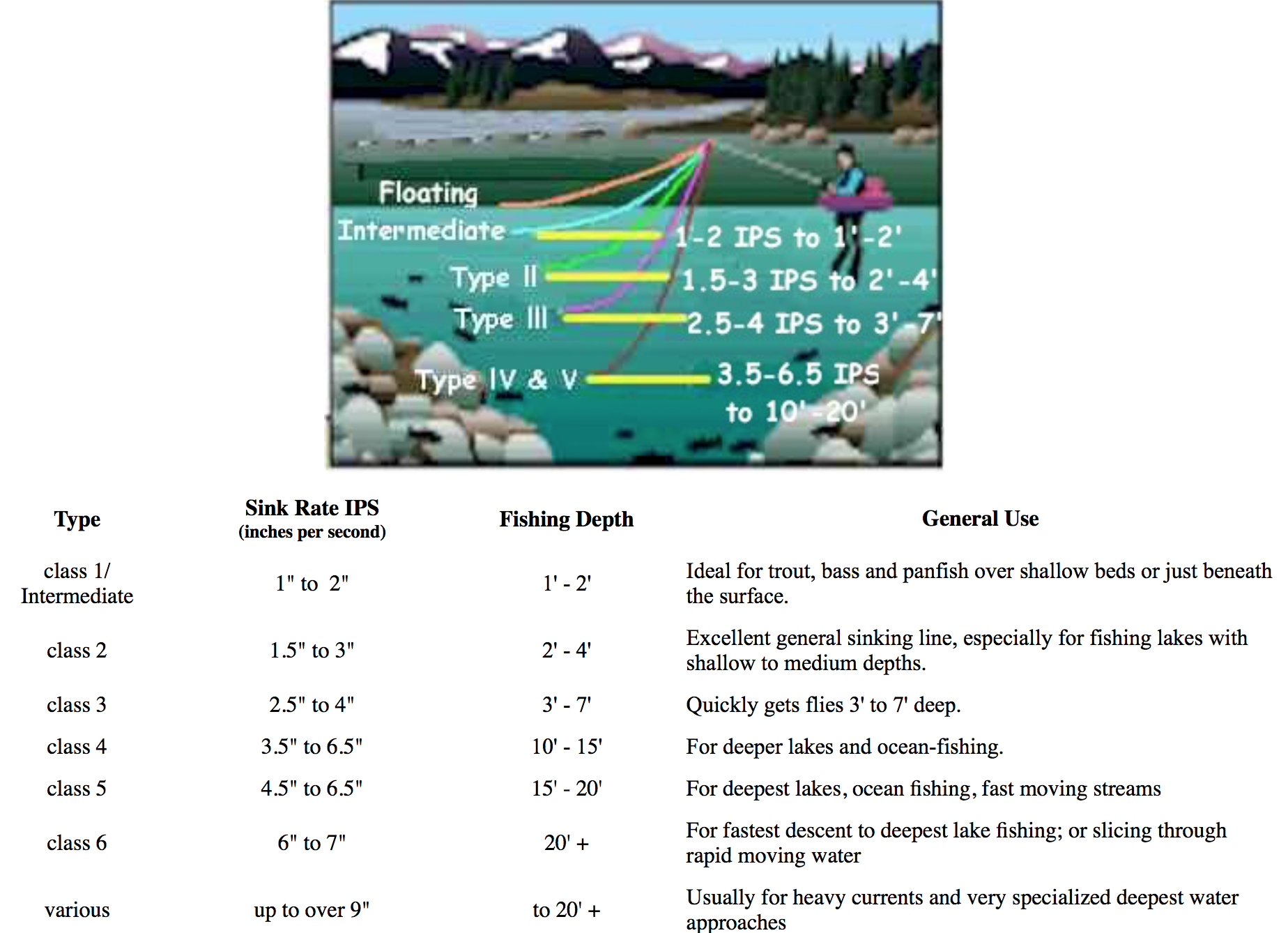

Sink tip fly lines have a number of variations. First, they will often have different lengths of sinking heads. In other words, the entire fly line will float except for the front 6’ or 15’ or whatever the case may be. In general, a shorter head will be easier to cast but a longer head will keep more of the line, and consequently the fly, down deeper. They will also come in different sink rates. Some manufacturers may provide a measurement in grains but most will be designated in a class – like a class 5. A Class 5, for instance, will typically sink at a rate of approximately 5” per second. A Class 2 will sink at approximately 2” per second. They commonly range from Class 1 (often described as an intermediate line) to Class 6.

Very often, the weight classes will correspond specifically with the actual line size. For instance, you may find a 10-weight sink tip line that is a Class 5, or a 6-weight sink tip line that is a Class 3, but there may not be an option for a Class 5 6-weight.

You can also find separate add-on sink tips to convert any floating line into a sink tip. This is convenient if you don’t want to carry an extra spool or if you don’t plan to fish sink tip lines frequently and don’t want the expense of an extra spool and line. However, my experience with these is that they hinge at the connection with the floating line and cast terribly.

You can also find separate add-on sink tips to convert any floating line into a sink tip. This is convenient if you don’t want to carry an extra spool or if you don’t plan to fish sink tip lines frequently and don’t want the expense of an extra spool and line. However, my experience with these is that they hinge at the connection with the floating line and cast terribly.

As with nearly everything in fly fishing, you need to figure out what’s best for your task at hand. Where are you going to be fishing? What are you trying to do? What size rod will you be using?

Hopefully, this sheds a little bit of light on sink tip lines. They can be terribly confusing, mainly because every manufacturer seems to have their own way of describing them. You really need to read through the fine print in the description of the lines to figure out what’s what. Your best bet is to talk to someone at a local fly shop who can really break down the differences for you.

Putting wet flies back into your fly box is a great way to not only rust the hook on that fly, but every fly around it. Utilizing some sort of fleece or foam fly patch on the exterior of your pack or vest to temporarily store flies as they dry will save you a lot of headaches (and money). An exterior fly patch also serves as a great “bullpen” for other flies you may want to to try through the day.

Putting wet flies back into your fly box is a great way to not only rust the hook on that fly, but every fly around it. Utilizing some sort of fleece or foam fly patch on the exterior of your pack or vest to temporarily store flies as they dry will save you a lot of headaches (and money). An exterior fly patch also serves as a great “bullpen” for other flies you may want to to try through the day. Once again, this is my variation of an existing pattern. Pat’s Rubber Legs is a stonefly pattern created by Idaho guide, Pat Bennett. If we’re keeping it real, Pat’s pattern is really just a variation of an older pattern called a Girdle Bug. I’ve talked about this before, but what constitutes and original fly pattern and what is simply a variation on an old standard is a REALLY fine line!

Once again, this is my variation of an existing pattern. Pat’s Rubber Legs is a stonefly pattern created by Idaho guide, Pat Bennett. If we’re keeping it real, Pat’s pattern is really just a variation of an older pattern called a Girdle Bug. I’ve talked about this before, but what constitutes and original fly pattern and what is simply a variation on an old standard is a REALLY fine line! The Overview: On December 3rd, the first ten people to book a guided trip or purchase a gift certificate for a guided trip will get a second guided trip free. If you’re not one of the first ten people, you can still buy one guided trip and get a second for 50% off anytime between December 3rd and December 24th. Just mention this offer.

The Overview: On December 3rd, the first ten people to book a guided trip or purchase a gift certificate for a guided trip will get a second guided trip free. If you’re not one of the first ten people, you can still buy one guided trip and get a second for 50% off anytime between December 3rd and December 24th. Just mention this offer. Caddis have always seemed to be one of the most overlooked and under-imitated aquatic insects in the fly fishing world. Maybe it’s because they haven’t been written about nearly as much as their sexier mayfly cousins over the years. I mean, mayflies are given names like Pale Morning Dun, Quill Gordon, and Gray Fox… just to name a few. Caddis are given names like Green Caddis, Brown Caddis, Black Caddis…

Caddis have always seemed to be one of the most overlooked and under-imitated aquatic insects in the fly fishing world. Maybe it’s because they haven’t been written about nearly as much as their sexier mayfly cousins over the years. I mean, mayflies are given names like Pale Morning Dun, Quill Gordon, and Gray Fox… just to name a few. Caddis are given names like Green Caddis, Brown Caddis, Black Caddis…

As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming.

As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming. Vests: For decades, this has been the standard for carrying fly boxes, tools, etc. on the stream and while there have been some changes over the years, the basic concept is still the same and this is still the choice for many anglers. One of the greatest benefits of a vest is that with individual pockets for nearly everything, it’s really easy to keep things separated and organized. And the design of the vest is such that you can keep most of those items quickly and easily accessible. Most vests will also have larger compartments on the back for items that you may not need to access as frequently, like a rain jacket or lunch. D-rings on the back of a vest also make a great place to attach a net where its out of the way but easily accessible with the addition of a magnetic or clip attachment.

Vests: For decades, this has been the standard for carrying fly boxes, tools, etc. on the stream and while there have been some changes over the years, the basic concept is still the same and this is still the choice for many anglers. One of the greatest benefits of a vest is that with individual pockets for nearly everything, it’s really easy to keep things separated and organized. And the design of the vest is such that you can keep most of those items quickly and easily accessible. Most vests will also have larger compartments on the back for items that you may not need to access as frequently, like a rain jacket or lunch. D-rings on the back of a vest also make a great place to attach a net where its out of the way but easily accessible with the addition of a magnetic or clip attachment. Hip Packs: These are often worn around the waist on the rear when not fishing, and rotated to the hip when accessing items in the pack. Probably their greatest advantage is that they stay out of your way when fishing and offer total freedom of movement when casting, etc. There are also accessories you can add (or may be built in to some packs) for carrying a net.

Hip Packs: These are often worn around the waist on the rear when not fishing, and rotated to the hip when accessing items in the pack. Probably their greatest advantage is that they stay out of your way when fishing and offer total freedom of movement when casting, etc. There are also accessories you can add (or may be built in to some packs) for carrying a net. Chest Packs: These, as the name implies, are designed to be worn on the chest and come in a number of sizes. They organize things in much the same way a hip pack does but keep things far more accessible on your chest and high out of the water. Many will have a D-ring on the rear of the neck strap for carrying a net. I would include a chest fly box (like I use) in the same category as a chest pack, except that there is no need for separate fly boxes.

Chest Packs: These, as the name implies, are designed to be worn on the chest and come in a number of sizes. They organize things in much the same way a hip pack does but keep things far more accessible on your chest and high out of the water. Many will have a D-ring on the rear of the neck strap for carrying a net. I would include a chest fly box (like I use) in the same category as a chest pack, except that there is no need for separate fly boxes.

Sling Packs: These are the latest trend in fishing packs and are designed to be more accessible than a hip pack and more out of the way than a chest pack. They are worn diagonally across your body so that they can be easily “slung” around to your front when you need to get to it. It can then be “slung” around and secured out of the way on your back when you’re fishing. They come in small and large sizes depending on how much you need to carry.

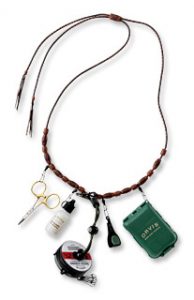

Sling Packs: These are the latest trend in fishing packs and are designed to be more accessible than a hip pack and more out of the way than a chest pack. They are worn diagonally across your body so that they can be easily “slung” around to your front when you need to get to it. It can then be “slung” around and secured out of the way on your back when you’re fishing. They come in small and large sizes depending on how much you need to carry. Lanyard: A fishing lanyard is basically a necklace for carrying your essentials around your neck. Most will comfortably carry and organize nippers, forceps, tippet, floatant and small fly box. By itself, this is for the absolute minimalist. For others, it may be a way to keep essential, frequently used items immediately accessible while carrying other less frequently used items in a hip pack or backpack.

Lanyard: A fishing lanyard is basically a necklace for carrying your essentials around your neck. Most will comfortably carry and organize nippers, forceps, tippet, floatant and small fly box. By itself, this is for the absolute minimalist. For others, it may be a way to keep essential, frequently used items immediately accessible while carrying other less frequently used items in a hip pack or backpack. My friend Walter Babb said that most people’s favorite fly is the fly they happened to have on the first day the fishing was really good. The implication of his statement is that more often than not, it’s the archer, not the arrow. Most of the time, if your fly is presented well and the fish are feeding, it probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on. And if the fish aren’t feeding? It probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on!

My friend Walter Babb said that most people’s favorite fly is the fly they happened to have on the first day the fishing was really good. The implication of his statement is that more often than not, it’s the archer, not the arrow. Most of the time, if your fly is presented well and the fish are feeding, it probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on. And if the fish aren’t feeding? It probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on!

While many anglers use them in different ways, liquid floatants are probably most useful before you ever get to the stream. Whether dry flies that you tie yourself or buy from a shop, you can use a liquid style floatant to “pre-treat” new flies in much the same way as you might “Scotchgard” your sofa. Exact application may vary and you should read the recommendations for the specific brand you purchase, but typically, flies will be soaked in the liquid for five minutes or so and then set out to dry overnight. In theory, after application of the product, water will better bead and roll of the fly material rather than absorb into it.

While many anglers use them in different ways, liquid floatants are probably most useful before you ever get to the stream. Whether dry flies that you tie yourself or buy from a shop, you can use a liquid style floatant to “pre-treat” new flies in much the same way as you might “Scotchgard” your sofa. Exact application may vary and you should read the recommendations for the specific brand you purchase, but typically, flies will be soaked in the liquid for five minutes or so and then set out to dry overnight. In theory, after application of the product, water will better bead and roll of the fly material rather than absorb into it. Gel floatants are probably the most common and popular style of floatant. They come in a small, very portable bottle and, like the liquid floatants, are designed to be a pre-treatment to an already dry fly. The big difference is gel floatants are designed to be used streamside, immediately before fishing the fly.

Gel floatants are probably the most common and popular style of floatant. They come in a small, very portable bottle and, like the liquid floatants, are designed to be a pre-treatment to an already dry fly. The big difference is gel floatants are designed to be used streamside, immediately before fishing the fly. Also normally applied while the fly is still dry, spray floatants are basically just a variation on a gel floatant. Spray floatants come in a bottle with a pump top and are applied much like you would spray something like an eyeglass cleaner. They are not as messy as the gel but are sometimes more challenging to completey coat the fly.

Also normally applied while the fly is still dry, spray floatants are basically just a variation on a gel floatant. Spray floatants come in a bottle with a pump top and are applied much like you would spray something like an eyeglass cleaner. They are not as messy as the gel but are sometimes more challenging to completey coat the fly. These are basically just a thicker version of a gel floatant. They can really create a mess on smaller dry flies and are probably best suited for larger dries like hoppers and stoneflies. A lot of people prefer a paste floatant to apply to yarn strike indicators or even on a leader to keep it floating better.

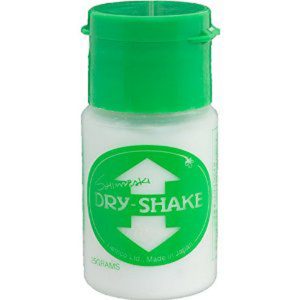

These are basically just a thicker version of a gel floatant. They can really create a mess on smaller dry flies and are probably best suited for larger dries like hoppers and stoneflies. A lot of people prefer a paste floatant to apply to yarn strike indicators or even on a leader to keep it floating better. These are used less as a pre-treatment and more as a means to revive a saturated fly. As mentioned above, when a dry fly becomes oversaturated and begins to sink, applying a gel or spray can often make it worse by trapping moisture in. Powder floatants are used to absorb and remove that moisture from a fly.

These are used less as a pre-treatment and more as a means to revive a saturated fly. As mentioned above, when a dry fly becomes oversaturated and begins to sink, applying a gel or spray can often make it worse by trapping moisture in. Powder floatants are used to absorb and remove that moisture from a fly. Brush floatants are essentially another version of a powder floatant. Rather than shaking the fly inside the bottle, a small brush is used to apply the powder to the fly. Again, it’s personal preference but with brush floatants, be prepared for a little frustration on windy days!

Brush floatants are essentially another version of a powder floatant. Rather than shaking the fly inside the bottle, a small brush is used to apply the powder to the fly. Again, it’s personal preference but with brush floatants, be prepared for a little frustration on windy days!