My friend Walter Babb said that most people’s favorite fly is the fly they happened to have on the first day the fishing was really good. The implication of his statement is that more often than not, it’s the archer, not the arrow. Most of the time, if your fly is presented well and the fish are feeding, it probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on. And if the fish aren’t feeding? It probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on!

My friend Walter Babb said that most people’s favorite fly is the fly they happened to have on the first day the fishing was really good. The implication of his statement is that more often than not, it’s the archer, not the arrow. Most of the time, if your fly is presented well and the fish are feeding, it probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on. And if the fish aren’t feeding? It probably doesn’t matter what fly you have on!

But since you happened to have that fly on the first day the fishing was good, you have confidence in it. Now it’s the first fly you put on and you leave it on longer. I have countless fly patterns that I abandoned because they didn’t catch fish the first time I tried them, but often that first time was after I tried everything else. Nothing was working that day!

With all of that said, I have, by far, caught more big brown trout in the Smokies on a Tellico Nymph than any other fly. But, you guessed it… the first big brown trout I caught in the Smokies was on a Tellico Nymph. I have confidence in it. And since most of the big browns I’ve taken over the years were either spotted first or caught during “favorable brown trout conditions,” I’d put a Tellico on in anticipation. So, it’s a bit deceiving. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those fish on a Prince Nymph had I chosen to tie one on?

Nevertheless, the Tellico Nymph is a good fly and it’s been around a long time. Its exact origins are unclear, though it was thought to have, obviously, been initially created and fished on the Tellico River in East Tennessee. It has definitely been around since the 1940’s, but some estimate that it may date back to the turn of the 20thcentury. In any case, it has to be the most well known fly from this region and it has accounted for fish all over the world.

In addition to its origin, there seems to be some confusion as to what the fly was originally supposed to imitate. Many contend that it represents a caddis larva. Others are just as certain it is supposed to be a mayfly nymph. To me, there is absolutely no doubt that it was intended to represent a golden stonefly nymph. The coloration and size are consistent with that of a golden stone, and the Tellico River has long been known for its abundance of these nymphs.

As with any popular fly that has been around for this long, there have been a number of variations on the pattern over the years. My personal favorite was devised by East Tennessee fly tyer, Rick Blackburn. I tie most in size #10.

Blackburn’s Tellico

Hook: 3XL nymph hook #12 – 6

Thread: Dark brown 6/0

Weight: .015 to .035 lead wire (depending on hook size)

Tail: Mink fibers (I often use moose as a substitute)

Rib: Gold wire and 2-3 strands of peacock herl

Wing Case: Section of turkey tail – lacquered

Body: Wapsi Stonefly Gold Life Cycle dubbing

Hackle: Brown Chinese neck hackle, palmered through thorax

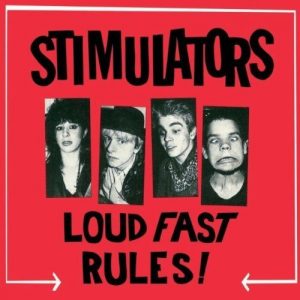

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

If you haven’t noticed by now, there are not a lot of “Hot New Flies” that I feature here. Most of the flies I fish with, particularly in the Smokies, are older, traditional patterns, or possibly an old staple that I’ve put a modern spin on. Maybe that makes me a curmudgeon. I don’t know. But until the old staples quit catching fish…

If you haven’t noticed by now, there are not a lot of “Hot New Flies” that I feature here. Most of the flies I fish with, particularly in the Smokies, are older, traditional patterns, or possibly an old staple that I’ve put a modern spin on. Maybe that makes me a curmudgeon. I don’t know. But until the old staples quit catching fish… No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves.

No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves. Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.

Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.