I once heard a highly regarded fly fisherman say that he considered polarized sunglasses to be his most important piece of gear. These sort of statements always amuse me because I can’t help to wonder how important those sunglasses would be if he didn’t have a rod or a line or a fly! But I definitely get what he meant. While polarized sunglasses may not be THE most important piece of gear, they are often the most underestimated by many fishermen.

Many fishermen, particularly those new to the sport, probably underestimate them because they don’t understand the difference in sunglasses and polarized sunglasses. They see sunglasses as merely a means of protecting your eyes from bright light and may opt not to wear them at all on overcast days or when fishing in shadier locations like the mountains. While polarized sunglasses do protect your eyes and reduce eyestrain in bright conditions, they have far greater importance when it comes to tactical applications.

Light usually scatters in all directions, but when it’s reflected from flat surfaces, it typically becomes polarized, travelling in a more uniform (usually horizontal) direction. This creates a serious intensity of reflected light that causes glare and reduces visibility. The more reflective that flat surface is, the more intense the glare will be – consider how a signaling mirror works.

Water has highly reflective properties and basically acts like a mirror that intensifies those reflected rays even more. I’m sure everyone can think of instances when driving where significant glare was encountered. More than likely, the worst glare you ever encountered when driving was during or right after a rain. Pavement is a flat surface that can reflect light and cause glare. Wet pavement intensifies that reflection and creates more intense glare. With that in mind, it stands to reason that you will get even more intense glare when light reflects off the surface of lakes, rivers, streams, etc.

So, “regular” sunglasses will help in these situations by essentially darkening this reflected light, making it less stressful to your eye, but the glare will still be there and will prohibit you from seeing anything on, or in the case of water, under that surface. But the chemical filter on the lenses of polarized sunglasses is designed to absorb horizontal light waves, while still allowing vertical waves to pass through. Because light only travels in one direction through polarized lenses, glare is eliminated, or at least reduced.

Contrary to what I believe many anglers expect, this technology does not create “magic fish-seeing glasses!” Fish will not suddenly be visible when you put on your polarized glasses, but with better ability to see through the water, you will be much better equipped to spot fish. However, the most consistent benefits you will receive from polarized glasses are the ability to better see your dry fly on the surface, and the ability to read water by better recognizing slower seams and deeper troughs and pockets. Additionally, being able to better see the stream bottom will allow for easier, safer wading.

Just how well your polarized glasses eliminate glare often depends on the angle the light hits and reflects off the water. There will be times on bright sunny days when the light reflects at such a severe angle that even the polarized lenses don’t seem to help. During these times, your best bet is to change the angle the light is hitting your eye by repositioning. For example, you may be on the left side of the stream facing and fishing toward the right and encounter an insurmountable amount of glare. Often by fishing from the other side of the stream and facing/fishing the other direction, you can totally eliminate the glare.

Even on overcast days or in shady areas, you can encounter significant glare, so I almost always wear polarized glasses when fishing. This is where lens color becomes important. Darker lens colors, like gray, will block more light, making them more ideal for bright conditions. They also work well on deep blue water and better maintain true color. But they block a little too much light in low light conditions like overcast, heavy shade, or dawn and dusk, which offsets the benefits of polarization.

Lighter lens colors, like yellow or rose, allow more light in and are perfect for fishing in low light conditions. They often even make things appear brighter. But in bright conditions, you want something that will filter light, not magnify it, so these are not good choices for sunny conditions on open water.

If you plan to fish a lot and expect to fish in a variety of different light conditions, you may find it beneficial to have multiple pairs of polarized glasses in different lens colors. But if you’re looking for one, multi-purpose lens color, an amber, copper or brown color sort of fits right in the middle. And these lens colors work particularly well in shallow water where most fly fishermen operate.

The shape of the frames can also be a factor in how well the glasses work. Frames that “wrap” more will help prevent direct and/or reflected light from entering on the sides. “Straight” frames, like an aviator style, allow more light in from side and rear angles. While prescription polarized sunglasses are available they can be problematic in a wrap style frame. Essentially, you’re dealing with a bent lens on a wrap style frame. The stronger the prescription and the more severe the bend in the lens, the more distortion you’ll get when looking side to side. Straight frames are better suited for prescription sunglasses.

If you wear corrective lenses and prefer the benefits of a wrap style frame or if you simply don’t want to fork over the money for prescription sunglasses, there are a number “fitover” sunglasses that are designed to be worn right over your regular eyeglasses.

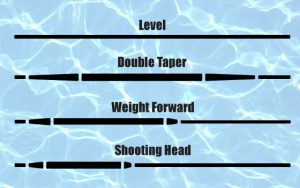

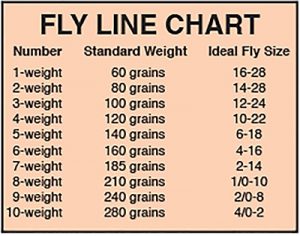

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.

In fly fishing, we’re using virtually weightless flies, many designed to float on the surface of the water. Even weighted flies that are designed to sink don’t have enough weight to carry themselves any sort of distance. We use the fly line for that. In essence, the fly line replaces the weight of a lure. When spin fishing, a weighted lure carries a weightless line when cast. In fly fishing, a weighted line carries a weightless lure.