When it comes to fishing dry flies in the Smokies, particularly on the smaller streams, I am typically looking for two primary things in a pattern: It needs to be visible and it needs to be buoyant. Beyond that I can begin focusing on a few more details like color and size.

In general, trout in the Smokies don’t see heavy hatches of individual insects. Rather, they mostly see small quantities of a lot of different insects. So, if you can present the fly naturally and without spooking fish, most any all-purpose, “prospecting” fly pattern will do the trick. As mentioned above, if you can get a little more precise with size and color, your pattern will be that much more effective.

Matching size will require more observation of bugs on the water or simply having general knowledge of what should be hatching. The same two things can help with matching color but also having broad knowledge of how seasons impact color can put you ahead of the curve. With some exceptions, aquatic insects tend to blend in with their surroundings. So, in winter months when trees are bare, most of what hatches is dark. As foliage comes in, most of what hatches is brighter.

The Stimulator has long been a favorite fly pattern of Smoky Mountain anglers for all of the reasons mentioned above. Its buoyancy and light colored wing not only make it easy to see, but make it a perfect “indicator fly” when fishing a dropper. And if you mix and match sizes and colors, you could nearly fish a Stimulator 12 months out of the year!

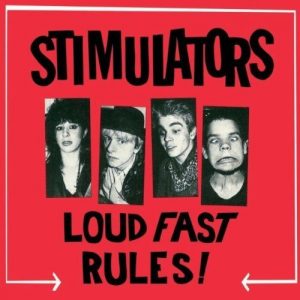

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

The Stimulator was long thought to be the invention of well-known West Coast angler and fly shop owner, Randall Kaufmann. While Kaufmann is responsible for the modifications that made the fly most of us know today, the fly’s true originator is thought to be Paul Slattery, who tied a stonefly pattern called the Fluttering Stonefly to fish on the Musconetcong River in central New Jersey. This was in the early 1980’s and he soon renamed the fly after a New York City punk-rock band called The Stimulators.

In any case, the fly seems to have been created to imitate an adult stonefly, but it is also a good suggestion of a caddis and sometimes even a hopper. I most often fish it in yellow and in sizes #16 – 8. I think the smaller size makes a great imitation for the prolific Little Yellow Sally Stoneflies, and the larger sizes are good representations of the larger golden stones that hatch on summer evenings in the mountains. In the fall, I often fish a #10 Stimulator in orange to imitate the large ginger caddis.

Whether it is imitating anything or not, it catches fish and it floats well in heavier pocket water found throughout the mountains. It is one of the most popular dry flies ever invented for trout and can be found in most every fly shop in the country.

Yellow Stimulator

Hook: Daiichi 1270 #16 – #10

Thread: 8/0 orange

Tail: Stacked elk hair

Abdomen: Yellow floss

Abdomen Hackle: Brown rooster neck – palmered

Wing: Stacked elk hair

Thorax: Bright orange dubbing

Thorax Hackle: Grizzly rooster neck – palmered

Learn more about Southern Appalachian fly patterns and hatches in my Hatch Guide.

Few fly fishermen, if any, possess the knowledge and experience of Joe Humphreys. Joe is probably best known as a teacher and an author, but over his many decades in the business, he has also created a number of original fly patterns. By far, my favorite is the Humphreys’ Caddis Pupa.

Few fly fishermen, if any, possess the knowledge and experience of Joe Humphreys. Joe is probably best known as a teacher and an author, but over his many decades in the business, he has also created a number of original fly patterns. By far, my favorite is the Humphreys’ Caddis Pupa.

So, I’m writing about March Browns not because they are necessarily of great significance to the Smoky Mountain fly fisherman, but mainly because they’re just really cool bugs! Like many aquatic insects in the Smokies, this mayfly does not usually hatch abundantly enough to really get the trout keyed in on them, but it is worth keeping a few in your fly box. In other words, you probably don’t need fifteen different March Brown patterns in subtly different colors. Having a few of a basic pattern should do the trick.

So, I’m writing about March Browns not because they are necessarily of great significance to the Smoky Mountain fly fisherman, but mainly because they’re just really cool bugs! Like many aquatic insects in the Smokies, this mayfly does not usually hatch abundantly enough to really get the trout keyed in on them, but it is worth keeping a few in your fly box. In other words, you probably don’t need fifteen different March Brown patterns in subtly different colors. Having a few of a basic pattern should do the trick.

If you take East Tennessee as a whole, it’s pretty safe to say one of the most prolific hatches is the sulphur mayfly hatch. Southern tailwaters are generally not known for having significant hatches of mayflies, caddisflies, or stoneflies. When we think of most of these dam-controlled rivers, we typically think of crustaceans like scuds and sow bugs, and midges…. lots and lots of midges. However, one mayfly that hatches on all East Tennessee tailwaters, often in very big numbers, is the sulphur. And that means that your best opportunity to catch a really big fish on a dry fly around these parts is during the sulphur hatch.

If you take East Tennessee as a whole, it’s pretty safe to say one of the most prolific hatches is the sulphur mayfly hatch. Southern tailwaters are generally not known for having significant hatches of mayflies, caddisflies, or stoneflies. When we think of most of these dam-controlled rivers, we typically think of crustaceans like scuds and sow bugs, and midges…. lots and lots of midges. However, one mayfly that hatches on all East Tennessee tailwaters, often in very big numbers, is the sulphur. And that means that your best opportunity to catch a really big fish on a dry fly around these parts is during the sulphur hatch.

If you haven’t noticed by now, there are not a lot of “Hot New Flies” that I feature here. Most of the flies I fish with, particularly in the Smokies, are older, traditional patterns, or possibly an old staple that I’ve put a modern spin on. Maybe that makes me a curmudgeon. I don’t know. But until the old staples quit catching fish…

If you haven’t noticed by now, there are not a lot of “Hot New Flies” that I feature here. Most of the flies I fish with, particularly in the Smokies, are older, traditional patterns, or possibly an old staple that I’ve put a modern spin on. Maybe that makes me a curmudgeon. I don’t know. But until the old staples quit catching fish… Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.

Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.

March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year.

March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year. Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.

Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.