If you’ve ever spent anytime fishing in the Smokies, you have missed plenty of strikes. And if you’ve ever been fishing with me in the Smokies, you’ve no doubt heard me say that no matter how good you are and how often you fish, you’re going to miss strikes from these fish. I’d say that’s true most anywhere, but in the Smokies, it’s a guarantee. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing for trout all over the United States and I am yet to find trout anywhere that hit and spit a fly quicker than they do in the Smokies! But while nobody is going to hook them all, there are plenty of things you can do to increase the number of fish you hook.

If you’ve ever spent anytime fishing in the Smokies, you have missed plenty of strikes. And if you’ve ever been fishing with me in the Smokies, you’ve no doubt heard me say that no matter how good you are and how often you fish, you’re going to miss strikes from these fish. I’d say that’s true most anywhere, but in the Smokies, it’s a guarantee. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing for trout all over the United States and I am yet to find trout anywhere that hit and spit a fly quicker than they do in the Smokies! But while nobody is going to hook them all, there are plenty of things you can do to increase the number of fish you hook.

Before we get into those things, let’s first talk about what exactly is going on when a trout hits your fly. I once guided a gentleman who was having an excellent day as far as activity goes, but he was missing A LOT of strikes. I was giving him plenty of tips along the way but midway through the day, I realized we just weren’t on the same page when, after missing another strike, he commented, “I don’t know how trout even survive.”

“What do you mean,” I asked.

He replied, “It seems like it would be hard for them to survive when they miss their food so often.”

I asked more emphatically this time, “What are you talking about?!?”

He said, “As often as they miss the fly, you know they’ve got to be missing the real food, too.”

I exclaimed, “They’re not missing. You are!”

Don’t get me wrong. I have missed plenty of strikes in my years of fly fishing. Like I said, we all do, but it’s always been my fault, not the trout’s! Sure, every now and then a fish will “short strike” the fly or bump it with his nose, but for most anglers, that is very much the exception. Even when that is the case, it’s probably still your fault. If you’re getting short strikes, it’s probably because your fly is too big, or your tippet is too big, or you have drag… Again, all of those things happen to everyone, but blaming the fish will never fix any of them!

So, what actually happens when a fish hits your fly? It depends on the kind of fly you’re fishing. When you are fishing a streamer (a fly that imitates a baitfish or something else that swims), you are usually stripping it and keeping a tight line. Typically, the trout will chase and/or ambush something they think is a wounded or fleeing baitfish. The strike will usually be rather aggressive and because you have a tight line, you will feel the strike. When you’re swinging wet flies or straight-line nymphing, you usually feel the strike as well, but it’s usually more subtle than the often violent strike that comes on a streamer.

But most of the time on a trout stream, most fly fishermen are imitating aquatic insects that are drifting in the water column. Whether adults on the surface or nymphs below the surface, these bugs are drifting helplessly in the current. When trout feed on these natural insects, it’s not necessary or efficient for them to swim around ambushing them. Rather, a trout will position facing a current, where the insects will drift down his feeding lane. All he has to do is maneuver slightly up, down, or to the side to pick them off. When a trout feeds in this manner, he’s more or less just moving in front of the bug and opening his mouth.

But most of the time on a trout stream, most fly fishermen are imitating aquatic insects that are drifting in the water column. Whether adults on the surface or nymphs below the surface, these bugs are drifting helplessly in the current. When trout feed on these natural insects, it’s not necessary or efficient for them to swim around ambushing them. Rather, a trout will position facing a current, where the insects will drift down his feeding lane. All he has to do is maneuver slightly up, down, or to the side to pick them off. When a trout feeds in this manner, he’s more or less just moving in front of the bug and opening his mouth.

But there are a lot of things coming down the current and some of them, like small twigs or leaves, may look like an insect to a trout. When he takes one of these foreign objects by mistake, he immediately spits it back out. It’s what a trout does all day. Real bug = swallow, stream junk that looks like a bug = spit it out. When you drift an artificial fly down the current and the trout hits it, he immediately spits it out because it’s not real. So you have that split second between when he eats it and when he spits it to set the hook.

Wild trout, like in the Smokies, are highly instinctive and tend to make this decision pretty quickly. Stocked trout were raised in hatcheries where they were fed daily. They tend to “trust” food a little more and consequently, will hold on to a foreign object (like your fly) a little longer before spitting it out. For that reason, fishermen tend to have a better strike to hook-up ratio on stocked trout vs. wild trout.

In either case, you are rarely going to feel the strike in these scenarios. To avoid drag and present the fly naturally, you will have to have some slack in your line and the fish doesn’t have the fly long enough to tighten your line enough for you to feel it. You will need to visually recognize the strike to tell you when to set the hook. With a dry fly, it’s fairly obvious because the fish will have to break the surface to eat your fly. As soon as you see that, set the hook. It is incredibly difficult in most situations to see a fish eat your nymph, so we often use a strike indicator positioned on the leader. When the fish eats the nymph, it will move the indicator, providing your visual cue to set the hook.

Now, with all of this in mind, here are some tips that may help you connect on a few more fish, particularly when dead-drifting dry flies and nymphs.

- Know that you will probably not feel the strike and trust the visual indication of the strike. Even when streamer fishing when you DO normally feel the strike, there are times when the fish hits between strips when the line is slack. You may not feel it but you’ll see the fly line dart forward. Trust what you see!

- Expect a strike every time the fly is on the water and be ready. As silly as it sounds, many strikes are missed because the fisherman just isn’t paying attention. Stay focused on what you’re doing. Don’t look at the bird overhead. Don’t look at the next pool up the river. Don’t stand there with your hand on your hip. Be ready!

- Similar to #2, pay attention to your slack. The cast isn’t when your job ends – it’s when it starts. Particularly when fishing upstream, be prepared to immediately begin collecting excess slack as it drifts back to you. Many fishermen think that they’re missing strikes because they’re too slow when, in fact, their reaction time is fine but they have too much slack to pick up to tighten on the fish. Leave just enough slack to achieve a good drift but no more.

- Keep your casts as short as possible. Not only will you be more accurate and probably get more strikes, but you’ll have less line to move when setting the hook. In some situations, like slow pools, we are forced to make long casts, but fish from better, closer positions when possible.

- Move the line. Your hook set should be like making a quick backcast. In other words, if you miss the strike, the line should go in the air behind you like a backcast. If you miss a strike and all of your line is still on the water in front of you, you didn’t move enough line to set the hook.

- Your hook set should be quick but smooth, and when possible, in an upward motion. A snappy or jerky hook set is a good way to break a tippet. A downward hook setting motion has a tendency to pull the fly out of the fish’s mouth, rather than up through the lip.

Setting the hook is also very much a timing thing. The more time you spend on the water, the better your timing will be and you may find that you sometimes even anticipate the strike just before it happens. And you may find that you have to adjust the timing of your hook set on different rivers. For instance, you may need to slow down a little when fishing for stockers or you may have to speed up a little when fishing for wild trout.

In either case, you’re still going to miss some and that’s okay. As far as fishing problems go, missing strikes is a pretty good one. To miss strikes you have to get strikes. And if you’re getting strikes, you’re doing something right!

Fly Tying is a lot like cooking in many ways. Of course, in both pursuits, you’re combining a variety of ingredients to create one final product. And the quality of those ingredients along with the skills of the person putting them together can tremendously impact the end result. But the issue of originality is also quite comparable.

Fly Tying is a lot like cooking in many ways. Of course, in both pursuits, you’re combining a variety of ingredients to create one final product. And the quality of those ingredients along with the skills of the person putting them together can tremendously impact the end result. But the issue of originality is also quite comparable.

I almost always fish with two flies when I’m trout fishing. There are just so many advantages to it. Beside the obvious advantage of potentially offering two fly choices to the trout, it provides you the opportunity to simultaneously present a fly in two different feeding columns. Below, I’m going to talk about some of those strategies as well as a few different ways to rig a dropper system. As a bonus, you get to enjoy some of my horrific artwork!

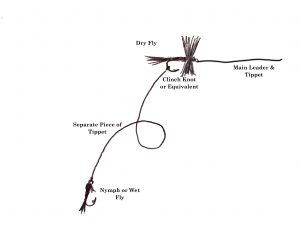

I almost always fish with two flies when I’m trout fishing. There are just so many advantages to it. Beside the obvious advantage of potentially offering two fly choices to the trout, it provides you the opportunity to simultaneously present a fly in two different feeding columns. Below, I’m going to talk about some of those strategies as well as a few different ways to rig a dropper system. As a bonus, you get to enjoy some of my horrific artwork! I typically rig this by tying my dry fly directly to the main leader and tippet. I’ll then take probably 18”-24” of tippet material and tie one end to the nymph, and the other to the bend of the hook on the dry fly. There are certainly a lot of variables, such as water depth or where you think the fish might be feeding, that determine how far apart you put the two flies, but the amount mentioned above is a pretty good “default setting.” I like to use a clinch knot to connect to the bend of the hook, but whatever knot you usually use to tie a fly on should work fine.

I typically rig this by tying my dry fly directly to the main leader and tippet. I’ll then take probably 18”-24” of tippet material and tie one end to the nymph, and the other to the bend of the hook on the dry fly. There are certainly a lot of variables, such as water depth or where you think the fish might be feeding, that determine how far apart you put the two flies, but the amount mentioned above is a pretty good “default setting.” I like to use a clinch knot to connect to the bend of the hook, but whatever knot you usually use to tie a fly on should work fine. With that in mind, know that this method may not be suitable for every situation. For instance, if you need to get a nymph deep, particularly in a faster run, you’re going to need a lot of weight and using a dry fly–dropper rig is not going to be effective. You’re better off using traditional nymphing techniques for that. But for fishing hatch scenarios where fish are actively feeding on and just below the surface, or for fishing to opportunistic feeders in shallower pocket water, it’s pretty tough to beat.

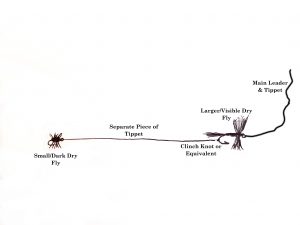

With that in mind, know that this method may not be suitable for every situation. For instance, if you need to get a nymph deep, particularly in a faster run, you’re going to need a lot of weight and using a dry fly–dropper rig is not going to be effective. You’re better off using traditional nymphing techniques for that. But for fishing hatch scenarios where fish are actively feeding on and just below the surface, or for fishing to opportunistic feeders in shallower pocket water, it’s pretty tough to beat. There are a few different ways to rig for this and there are numerous strategies for fly selection and placement. If I have a nymph pattern that the fish are really after, I will sometimes fish two of the exact same fly. There have even been a few occasions when I’ve caught two fish at once! But usually I’m searching and I’m trying to provide the fish with options, so I’ll most often have two different fly patterns.

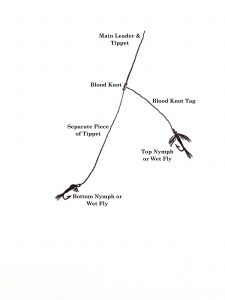

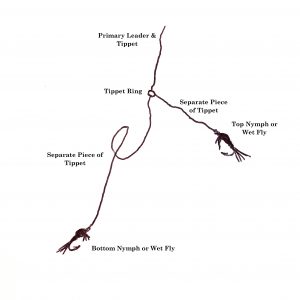

There are a few different ways to rig for this and there are numerous strategies for fly selection and placement. If I have a nymph pattern that the fish are really after, I will sometimes fish two of the exact same fly. There have even been a few occasions when I’ve caught two fish at once! But usually I’m searching and I’m trying to provide the fish with options, so I’ll most often have two different fly patterns. A common way to rig two nymphs that will allow the top fly to drift more freely, is to use a blood knot to attach a section of tippet to the end of your leader. When tying the knot, take care to leave one long tag end, to which you will tie the top fly. The bottom fly will be attached to the end of the new tippet section. This definitely allows the top fly to have more movement and it puts you in more direct contact with both nymphs. Though for me, this method results in a lot more tangles so I only use it for specific scenarios.

A common way to rig two nymphs that will allow the top fly to drift more freely, is to use a blood knot to attach a section of tippet to the end of your leader. When tying the knot, take care to leave one long tag end, to which you will tie the top fly. The bottom fly will be attached to the end of the new tippet section. This definitely allows the top fly to have more movement and it puts you in more direct contact with both nymphs. Though for me, this method results in a lot more tangles so I only use it for specific scenarios. So, I’m writing about March Browns not because they are necessarily of great significance to the Smoky Mountain fly fisherman, but mainly because they’re just really cool bugs! Like many aquatic insects in the Smokies, this mayfly does not usually hatch abundantly enough to really get the trout keyed in on them, but it is worth keeping a few in your fly box. In other words, you probably don’t need fifteen different March Brown patterns in subtly different colors. Having a few of a basic pattern should do the trick.

So, I’m writing about March Browns not because they are necessarily of great significance to the Smoky Mountain fly fisherman, but mainly because they’re just really cool bugs! Like many aquatic insects in the Smokies, this mayfly does not usually hatch abundantly enough to really get the trout keyed in on them, but it is worth keeping a few in your fly box. In other words, you probably don’t need fifteen different March Brown patterns in subtly different colors. Having a few of a basic pattern should do the trick.

Probably 20 years ago, I was fishing the Clinch River with a buddy during the sulfur hatch. I won’t get into what has happened to that hatch, but back then, it was epic. Sulfurs would come off by the thousands for 4-6 hours a day for about 3 months. We would drive down from Kentucky to fish it and on most trips, we would both steadily catch fish, many topping 20”.

Probably 20 years ago, I was fishing the Clinch River with a buddy during the sulfur hatch. I won’t get into what has happened to that hatch, but back then, it was epic. Sulfurs would come off by the thousands for 4-6 hours a day for about 3 months. We would drive down from Kentucky to fish it and on most trips, we would both steadily catch fish, many topping 20”.

If fish are actively rising but you don’t see any bugs in the air, check the water. Try to position yourself at the bottom of a feeding lane (downstream of where the fish are feeding) and watch the surface of the water (and just beneath) for drifting bugs. Holding a fine mesh net in the current is a great way to collect what’s coming down the channel, but if you don’t have one, your eyeballs will do just fine. If you see some insects, capture one and try to match it with a fly pattern.

If fish are actively rising but you don’t see any bugs in the air, check the water. Try to position yourself at the bottom of a feeding lane (downstream of where the fish are feeding) and watch the surface of the water (and just beneath) for drifting bugs. Holding a fine mesh net in the current is a great way to collect what’s coming down the channel, but if you don’t have one, your eyeballs will do just fine. If you see some insects, capture one and try to match it with a fly pattern. When I first started fly fishing, it was a different time. It was before everyone had access to the Internet. There were no message boards. There was no Twitter. There was no Facebook. Many fisheries didn’t receive nearly as much pressure simply because not nearly as many people knew about them. And to the fishermen who did know about them, they were closely guarded secrets shared only with a handful of trusted friends.

When I first started fly fishing, it was a different time. It was before everyone had access to the Internet. There were no message boards. There was no Twitter. There was no Facebook. Many fisheries didn’t receive nearly as much pressure simply because not nearly as many people knew about them. And to the fishermen who did know about them, they were closely guarded secrets shared only with a handful of trusted friends.

If you’ve ever spent anytime fishing in the Smokies, you have missed plenty of strikes. And if you’ve ever been fishing with me in the Smokies, you’ve no doubt heard me say that no matter how good you are and how often you fish, you’re going to miss strikes from these fish. I’d say that’s true most anywhere, but in the Smokies, it’s a guarantee. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing for trout all over the United States and I am yet to find trout anywhere that hit and spit a fly quicker than they do in the Smokies! But while nobody is going to hook them all, there are plenty of things you can do to increase the number of fish you hook.

If you’ve ever spent anytime fishing in the Smokies, you have missed plenty of strikes. And if you’ve ever been fishing with me in the Smokies, you’ve no doubt heard me say that no matter how good you are and how often you fish, you’re going to miss strikes from these fish. I’d say that’s true most anywhere, but in the Smokies, it’s a guarantee. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing for trout all over the United States and I am yet to find trout anywhere that hit and spit a fly quicker than they do in the Smokies! But while nobody is going to hook them all, there are plenty of things you can do to increase the number of fish you hook. But most of the time on a trout stream, most fly fishermen are imitating aquatic insects that are drifting in the water column. Whether adults on the surface or nymphs below the surface, these bugs are drifting helplessly in the current. When trout feed on these natural insects, it’s not necessary or efficient for them to swim around ambushing them. Rather, a trout will position facing a current, where the insects will drift down his feeding lane. All he has to do is maneuver slightly up, down, or to the side to pick them off. When a trout feeds in this manner, he’s more or less just moving in front of the bug and opening his mouth.

But most of the time on a trout stream, most fly fishermen are imitating aquatic insects that are drifting in the water column. Whether adults on the surface or nymphs below the surface, these bugs are drifting helplessly in the current. When trout feed on these natural insects, it’s not necessary or efficient for them to swim around ambushing them. Rather, a trout will position facing a current, where the insects will drift down his feeding lane. All he has to do is maneuver slightly up, down, or to the side to pick them off. When a trout feeds in this manner, he’s more or less just moving in front of the bug and opening his mouth.

If you take East Tennessee as a whole, it’s pretty safe to say one of the most prolific hatches is the sulphur mayfly hatch. Southern tailwaters are generally not known for having significant hatches of mayflies, caddisflies, or stoneflies. When we think of most of these dam-controlled rivers, we typically think of crustaceans like scuds and sow bugs, and midges…. lots and lots of midges. However, one mayfly that hatches on all East Tennessee tailwaters, often in very big numbers, is the sulphur. And that means that your best opportunity to catch a really big fish on a dry fly around these parts is during the sulphur hatch.

If you take East Tennessee as a whole, it’s pretty safe to say one of the most prolific hatches is the sulphur mayfly hatch. Southern tailwaters are generally not known for having significant hatches of mayflies, caddisflies, or stoneflies. When we think of most of these dam-controlled rivers, we typically think of crustaceans like scuds and sow bugs, and midges…. lots and lots of midges. However, one mayfly that hatches on all East Tennessee tailwaters, often in very big numbers, is the sulphur. And that means that your best opportunity to catch a really big fish on a dry fly around these parts is during the sulphur hatch.

In the last ten years or so, the term “Euro Nymphing” or “Czech Nymphing” has become more and more common, and is often billed as a revolutionary style of fishing. Basically, it is just nymph fishing without a strike indicator. It’s akin to what many for years have referred to as short-line or straight-line nymphing. Others refer to it as high-sticking. Or the old mountain fishermen around here just call it nymphing, because it’s how they’ve fished for decades and decades.

In the last ten years or so, the term “Euro Nymphing” or “Czech Nymphing” has become more and more common, and is often billed as a revolutionary style of fishing. Basically, it is just nymph fishing without a strike indicator. It’s akin to what many for years have referred to as short-line or straight-line nymphing. Others refer to it as high-sticking. Or the old mountain fishermen around here just call it nymphing, because it’s how they’ve fished for decades and decades. We often hear about the importance of fishing terrestrials in the summer months. Out west, the conversation usually focuses on hoppers. Around here, we talk more about beetles, ants, and inchworms. Regardless, there are a number of land-based insects from beetles, ants and hoppers to cicadas, bees and black flies that find their way into the water during the summer months.

We often hear about the importance of fishing terrestrials in the summer months. Out west, the conversation usually focuses on hoppers. Around here, we talk more about beetles, ants, and inchworms. Regardless, there are a number of land-based insects from beetles, ants and hoppers to cicadas, bees and black flies that find their way into the water during the summer months.