I almost always fish with two flies when I’m trout fishing. There are just so many advantages to it. Beside the obvious advantage of potentially offering two fly choices to the trout, it provides you the opportunity to simultaneously present a fly in two different feeding columns. Below, I’m going to talk about some of those strategies as well as a few different ways to rig a dropper system. As a bonus, you get to enjoy some of my horrific artwork!

I almost always fish with two flies when I’m trout fishing. There are just so many advantages to it. Beside the obvious advantage of potentially offering two fly choices to the trout, it provides you the opportunity to simultaneously present a fly in two different feeding columns. Below, I’m going to talk about some of those strategies as well as a few different ways to rig a dropper system. As a bonus, you get to enjoy some of my horrific artwork!

Dry Fly / Dropper

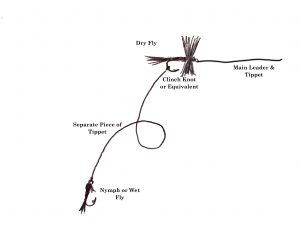

This is the two-fly method with which many fly fishermen are most familiar. It seems that even less experienced fishermen will tell you this is how their guide rigged them up when they were fishing out west during hopper season. When you rig like this, you are typically tying on a larger, or at least more visible, dry fly and attaching a smaller nymph off the back of that dry fly. You’re covering the top of the water with the dry fly and you’re covering usually the middle water column (sometimes the bottom) with the nymph. The dry fly serves as sort of an edible strike indicator for the nymph.

I typically rig this by tying my dry fly directly to the main leader and tippet. I’ll then take probably 18”-24” of tippet material and tie one end to the nymph, and the other to the bend of the hook on the dry fly. There are certainly a lot of variables, such as water depth or where you think the fish might be feeding, that determine how far apart you put the two flies, but the amount mentioned above is a pretty good “default setting.” I like to use a clinch knot to connect to the bend of the hook, but whatever knot you usually use to tie a fly on should work fine.

I typically rig this by tying my dry fly directly to the main leader and tippet. I’ll then take probably 18”-24” of tippet material and tie one end to the nymph, and the other to the bend of the hook on the dry fly. There are certainly a lot of variables, such as water depth or where you think the fish might be feeding, that determine how far apart you put the two flies, but the amount mentioned above is a pretty good “default setting.” I like to use a clinch knot to connect to the bend of the hook, but whatever knot you usually use to tie a fly on should work fine.

You want to make sure that the flies you select for this set-up compliment each other and are appropriate for the type of water you’re fishing. For example, a small parachute dry fly may not support the weight of a large, heavily weighted nymph. Parachute type patterns will easily support the weight of smaller, lighter nymphs, particularly in slower water. So, a #14 Parachute Adams with a #18 Zebra Midge dropper would be great for a tailwater or maybe a slower run or pool in the mountains. A #14 Parachute Adams with a #8 weighted Tellico nymph, fished in faster water is going to be trouble. Heavily hackled, bushy dry flies or foam dry flies are better choices when fishing in faster water or with heavier nymphs.

With that in mind, know that this method may not be suitable for every situation. For instance, if you need to get a nymph deep, particularly in a faster run, you’re going to need a lot of weight and using a dry fly–dropper rig is not going to be effective. You’re better off using traditional nymphing techniques for that. But for fishing hatch scenarios where fish are actively feeding on and just below the surface, or for fishing to opportunistic feeders in shallower pocket water, it’s pretty tough to beat.

With that in mind, know that this method may not be suitable for every situation. For instance, if you need to get a nymph deep, particularly in a faster run, you’re going to need a lot of weight and using a dry fly–dropper rig is not going to be effective. You’re better off using traditional nymphing techniques for that. But for fishing hatch scenarios where fish are actively feeding on and just below the surface, or for fishing to opportunistic feeders in shallower pocket water, it’s pretty tough to beat.

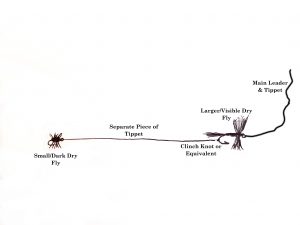

I also like to fish this same rig with two dry fly flies. On many occasions, I’ve found myself in a situation where I have trouble seeing my dry fly – usually when trying to imitate something small or dark like a midge, Trico, or BWO. In those situations, I’ll often tie on a larger, more visible dry fly with the smaller, darker dry fly tied about 18” off the back. Sometimes, having the more visible fly as reference allows me to actually see the smaller fly. But if I still can’t see the smaller one, I know to set the hook if I see a rise anywhere within 18” of the visible fly.

Two Nymphs or Wet Flies

Just like the dry fly-dropper rig above, fishing with two nymphs or wets allows you to cover two different feeding columns. Only now, you’re typically covering the middle column and the bottom. I think another advantage with a two nymph rig is they tend to balance each other out and drift better.

There are a few different ways to rig for this and there are numerous strategies for fly selection and placement. If I have a nymph pattern that the fish are really after, I will sometimes fish two of the exact same fly. There have even been a few occasions when I’ve caught two fish at once! But usually I’m searching and I’m trying to provide the fish with options, so I’ll most often have two different fly patterns.

There are a few different ways to rig for this and there are numerous strategies for fly selection and placement. If I have a nymph pattern that the fish are really after, I will sometimes fish two of the exact same fly. There have even been a few occasions when I’ve caught two fish at once! But usually I’m searching and I’m trying to provide the fish with options, so I’ll most often have two different fly patterns.

Keep in mind that (most of the time) your lowest fly on the rig will be fished near the bottom while the higher fly will be fished more in the middle column. I try to select and position flies with that in mind. For example, it’s far less likely to find a stonefly in the middle of the water column. They’re going to be found near the stream bottom, so logically, I want my stonefly nymph to be the bottom fly of my two fly rig. On the other hand, an emerging mayfly is more likely to be found in the middle feeding column. So, a soft hackle wet fly would probably be most effective as the top fly on my nymph rig.

You can rig like this with totally different flies or you may decide to stay in the same “family.” If you’re in the middle of or expecting, say, a caddis hatch, you may rig with a caddis emerger as your top fly and a caddis larva as your bottom fly. I’ve also had a lot of success choosing one nymph to act purely as an attractor. I may tie on a larger or brighter nymph as my top fly and a smaller or subtler nymph as my bottom one. I think that very often, the brighter or bigger nymph gets their attention, but they eat the subtler nymph below it. I tend to fish the nymphs a little closer together in these situations.

You can rig a pair of nymphs the same way we mentioned above, by tying one directly off the hook bend of the other – referred to as the in-line method. This is probably the easiest way to rig and fish two nymphs. But some don’t like this method because they don’t think it allows the top fly to drift freely.

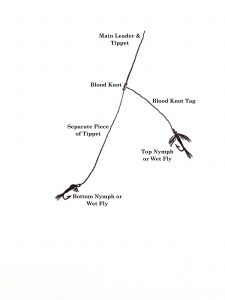

A common way to rig two nymphs that will allow the top fly to drift more freely, is to use a blood knot to attach a section of tippet to the end of your leader. When tying the knot, take care to leave one long tag end, to which you will tie the top fly. The bottom fly will be attached to the end of the new tippet section. This definitely allows the top fly to have more movement and it puts you in more direct contact with both nymphs. Though for me, this method results in a lot more tangles so I only use it for specific scenarios.

A common way to rig two nymphs that will allow the top fly to drift more freely, is to use a blood knot to attach a section of tippet to the end of your leader. When tying the knot, take care to leave one long tag end, to which you will tie the top fly. The bottom fly will be attached to the end of the new tippet section. This definitely allows the top fly to have more movement and it puts you in more direct contact with both nymphs. Though for me, this method results in a lot more tangles so I only use it for specific scenarios.

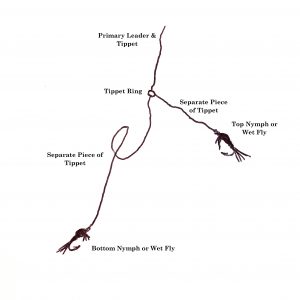

You can also rig quite similarly using a tippet ring (discussed in another article in this newsletter). With a tippet ring attached to the end of your leader, you tie one shorter piece of tippet to the ring, to which you will tie your top fly. And you tie a separate, longer piece of tippet to the ring, to which you’ll tie your bottom fly. This is a pretty simple way to do things but will also likely result in a few more tangles than the in-line method.

These are just examples of a few of the more common methods for fishing and rigging multiple flies. Play around with it and find what combos and techniques work best for you. Never be afraid to experiment!

Rob, when fishing a two fly rig are there any special things to look out for when casting? I know that I’ve had issues in the past with my tailing fly getting wrapped up around the dry. I’m sure it is a flaw in my cast, but it seems that when I’m fishing tandem rigs I have to pay a lot closer attention to my cast.

Hey Kelly,

Great question. No matter how you slice it, the more stuff you put on a line: droppers, indicators, split shot, etc. the greater the chance of tangles! Certainly, it could be a glitch in your cast. If you’re prone to tailing loops, you might see frequent “wind knots” in your line with a single fly. With a dropper added, wind knots become full blown tangles.

With that said, I don’t typically alter my cast much, if at all, when fishing a dry fly-dropper rig. However, when fishing extra weight, like two nymphs, particularly heavy nymphs, or extra split shot, it can be difficult for the fly line to effectively turn the flies over during the cast. Often the flies will travel below the fly line and can get tangled up. There are a few casting solutions to this but the simplest is to throw a wider casting loop. Again, there are a few ways to accomplish this but the easiest is to bring your rod slightly farther back on the back cast so that your rod tip travels less on a straight line path and more in a slight arc.

Hopefully this helps a little. Explaining casting through text is challenging. I will soon be adding videos to the blog/newsletter and will definitely demonstrate many of these things there!