As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming.

As with most things in fly fishing, fishing packs and vests have come a long way over the years. The great thing about that is you now have a seemingly endless array of ways to carry and organize your on-stream tools and accessories. The bad thing is those seemingly endless choices can be a bit overwhelming.

There is certainly no right or wrong pack or vest. The best option for you will boil down to how much stuff you plan to carry, where you plan to carry it (backcountry or more roadside), and how you want to organize it. As with fly rods, the more diverse your fishing adventures are, the more likely you’ll need more than one option. For instance, what might work well for backcountry trout fishing in the mountains may not work very well wading saltwater flats. But for most folks, you should be able to find one system that works for all of your fishing needs.

Again, what works best for me may not suit you at all, so I’m not going to try to tell you the best product. However, I have had the opportunity over the last 30 years to use most every style of vest/pack and will share below what I believe are pros and cons of each.

Vests: For decades, this has been the standard for carrying fly boxes, tools, etc. on the stream and while there have been some changes over the years, the basic concept is still the same and this is still the choice for many anglers. One of the greatest benefits of a vest is that with individual pockets for nearly everything, it’s really easy to keep things separated and organized. And the design of the vest is such that you can keep most of those items quickly and easily accessible. Most vests will also have larger compartments on the back for items that you may not need to access as frequently, like a rain jacket or lunch. D-rings on the back of a vest also make a great place to attach a net where its out of the way but easily accessible with the addition of a magnetic or clip attachment.

Vests: For decades, this has been the standard for carrying fly boxes, tools, etc. on the stream and while there have been some changes over the years, the basic concept is still the same and this is still the choice for many anglers. One of the greatest benefits of a vest is that with individual pockets for nearly everything, it’s really easy to keep things separated and organized. And the design of the vest is such that you can keep most of those items quickly and easily accessible. Most vests will also have larger compartments on the back for items that you may not need to access as frequently, like a rain jacket or lunch. D-rings on the back of a vest also make a great place to attach a net where its out of the way but easily accessible with the addition of a magnetic or clip attachment.

While there have been numerous improvements over the years, the biggest complaint with vests still seems to be that they are heavy, with most of the weight being carried on your neck and shoulders. Another downside is they do not wear well with a backpack. If you like to do a lot of backcountry fishing, you may want to carry more safety and comfort provisions that necessitate a backpack in addition to your fishing gear. It can be difficult to comfortably and practically wear a backpack when the straps are going over full, bulky pockets on a vest.

Hip Packs: These are often worn around the waist on the rear when not fishing, and rotated to the hip when accessing items in the pack. Probably their greatest advantage is that they stay out of your way when fishing and offer total freedom of movement when casting, etc. There are also accessories you can add (or may be built in to some packs) for carrying a net.

Hip Packs: These are often worn around the waist on the rear when not fishing, and rotated to the hip when accessing items in the pack. Probably their greatest advantage is that they stay out of your way when fishing and offer total freedom of movement when casting, etc. There are also accessories you can add (or may be built in to some packs) for carrying a net.

The biggest downside to a hip pack is that it doesn’t keep items as organized and it can be more difficult to access those items. Additionally, the hip pack, by itself, usually does not have the capacity to carry larger items like a rain jacket or lunch. However, a hip pack does wear comfortably with an additional backpack. Many will use the hip pack alone when fishing closer to the car and add a backpack when fishing in the backcountry. Finally, these are not the best option for someone who does a lot of deep wading. Although, there are a lot of waterproof options now.

Chest Packs: These, as the name implies, are designed to be worn on the chest and come in a number of sizes. They organize things in much the same way a hip pack does but keep things far more accessible on your chest and high out of the water. Many will have a D-ring on the rear of the neck strap for carrying a net. I would include a chest fly box (like I use) in the same category as a chest pack, except that there is no need for separate fly boxes.

Chest Packs: These, as the name implies, are designed to be worn on the chest and come in a number of sizes. They organize things in much the same way a hip pack does but keep things far more accessible on your chest and high out of the water. Many will have a D-ring on the rear of the neck strap for carrying a net. I would include a chest fly box (like I use) in the same category as a chest pack, except that there is no need for separate fly boxes.

Some don’t like having a cumbersome item on their chest and some of the larger chest packs can be quite cumbersome. Smaller chest packs are very comfortable but don’t carry as much stuff. In either case, you won’t have enough capacity to carry large items but like a hip pack, you can easily wear a backpack with your chest pack to carry more things when travelling far from the car. Some companies even make “fishing backpacks” designed in such a way that a compatible chest pack can clip to the front of it.

Sling Packs: These are the latest trend in fishing packs and are designed to be more accessible than a hip pack and more out of the way than a chest pack. They are worn diagonally across your body so that they can be easily “slung” around to your front when you need to get to it. It can then be “slung” around and secured out of the way on your back when you’re fishing. They come in small and large sizes depending on how much you need to carry.

Sling Packs: These are the latest trend in fishing packs and are designed to be more accessible than a hip pack and more out of the way than a chest pack. They are worn diagonally across your body so that they can be easily “slung” around to your front when you need to get to it. It can then be “slung” around and secured out of the way on your back when you’re fishing. They come in small and large sizes depending on how much you need to carry.

These packs are well designed and very comfortable but even the big ones don’t have enough capacity to carry everything you might want to take on a trip deep into the backcountry. On such a trip, I typically carry a rain jacket, lunch, first-aid kit and plenty of water. I also regularly carry my wading boots in on long hikes. You need a backpack to carry those items and a sling bag just can’t be worn and utilized with a backpack. The other downside to a sling bag is there just doesn’t seem to be a good place to carry a net (if needed) without it getting in the way.

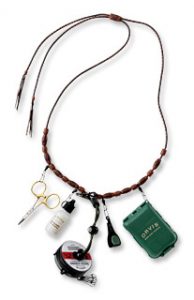

Lanyard: A fishing lanyard is basically a necklace for carrying your essentials around your neck. Most will comfortably carry and organize nippers, forceps, tippet, floatant and small fly box. By itself, this is for the absolute minimalist. For others, it may be a way to keep essential, frequently used items immediately accessible while carrying other less frequently used items in a hip pack or backpack.

Lanyard: A fishing lanyard is basically a necklace for carrying your essentials around your neck. Most will comfortably carry and organize nippers, forceps, tippet, floatant and small fly box. By itself, this is for the absolute minimalist. For others, it may be a way to keep essential, frequently used items immediately accessible while carrying other less frequently used items in a hip pack or backpack.

The downside is fairly obvious with a lanyard. It has almost zero capacity. There is no place for rain jacket, lunch, water, camera, leaders, multiple fly boxes, etc. In my opinion, the only reasonable use for a lanyard would be in a boat or in conjunction with another pack as mentioned above.

While many anglers use them in different ways, liquid floatants are probably most useful before you ever get to the stream. Whether dry flies that you tie yourself or buy from a shop, you can use a liquid style floatant to “pre-treat” new flies in much the same way as you might “Scotchgard” your sofa. Exact application may vary and you should read the recommendations for the specific brand you purchase, but typically, flies will be soaked in the liquid for five minutes or so and then set out to dry overnight. In theory, after application of the product, water will better bead and roll of the fly material rather than absorb into it.

While many anglers use them in different ways, liquid floatants are probably most useful before you ever get to the stream. Whether dry flies that you tie yourself or buy from a shop, you can use a liquid style floatant to “pre-treat” new flies in much the same way as you might “Scotchgard” your sofa. Exact application may vary and you should read the recommendations for the specific brand you purchase, but typically, flies will be soaked in the liquid for five minutes or so and then set out to dry overnight. In theory, after application of the product, water will better bead and roll of the fly material rather than absorb into it. Gel floatants are probably the most common and popular style of floatant. They come in a small, very portable bottle and, like the liquid floatants, are designed to be a pre-treatment to an already dry fly. The big difference is gel floatants are designed to be used streamside, immediately before fishing the fly.

Gel floatants are probably the most common and popular style of floatant. They come in a small, very portable bottle and, like the liquid floatants, are designed to be a pre-treatment to an already dry fly. The big difference is gel floatants are designed to be used streamside, immediately before fishing the fly. Also normally applied while the fly is still dry, spray floatants are basically just a variation on a gel floatant. Spray floatants come in a bottle with a pump top and are applied much like you would spray something like an eyeglass cleaner. They are not as messy as the gel but are sometimes more challenging to completey coat the fly.

Also normally applied while the fly is still dry, spray floatants are basically just a variation on a gel floatant. Spray floatants come in a bottle with a pump top and are applied much like you would spray something like an eyeglass cleaner. They are not as messy as the gel but are sometimes more challenging to completey coat the fly. These are basically just a thicker version of a gel floatant. They can really create a mess on smaller dry flies and are probably best suited for larger dries like hoppers and stoneflies. A lot of people prefer a paste floatant to apply to yarn strike indicators or even on a leader to keep it floating better.

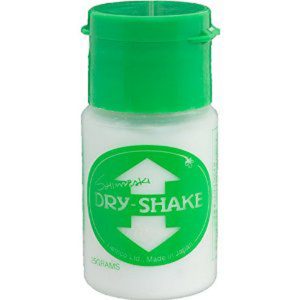

These are basically just a thicker version of a gel floatant. They can really create a mess on smaller dry flies and are probably best suited for larger dries like hoppers and stoneflies. A lot of people prefer a paste floatant to apply to yarn strike indicators or even on a leader to keep it floating better. These are used less as a pre-treatment and more as a means to revive a saturated fly. As mentioned above, when a dry fly becomes oversaturated and begins to sink, applying a gel or spray can often make it worse by trapping moisture in. Powder floatants are used to absorb and remove that moisture from a fly.

These are used less as a pre-treatment and more as a means to revive a saturated fly. As mentioned above, when a dry fly becomes oversaturated and begins to sink, applying a gel or spray can often make it worse by trapping moisture in. Powder floatants are used to absorb and remove that moisture from a fly. Brush floatants are essentially another version of a powder floatant. Rather than shaking the fly inside the bottle, a small brush is used to apply the powder to the fly. Again, it’s personal preference but with brush floatants, be prepared for a little frustration on windy days!

Brush floatants are essentially another version of a powder floatant. Rather than shaking the fly inside the bottle, a small brush is used to apply the powder to the fly. Again, it’s personal preference but with brush floatants, be prepared for a little frustration on windy days!

Over the last few years, tippet rings have been gaining more and more popularity and acceptance. Most new fly fishermen love them. Most traditionalists hate them. What are they?

Over the last few years, tippet rings have been gaining more and more popularity and acceptance. Most new fly fishermen love them. Most traditionalists hate them. What are they?

I recently saw a post on Facebook from a gentleman who had broken two fly rods on one trip. Another person commented about “having the record” for taking the most broken rods back to his local fly shop. They proceeded to boastfully go back and forth about this as if it was some sort of badge of honor. Accidents happen and rods do break from time to time, but I had guided one of these gentlemen and it was no secret why he had broken so many.

I recently saw a post on Facebook from a gentleman who had broken two fly rods on one trip. Another person commented about “having the record” for taking the most broken rods back to his local fly shop. They proceeded to boastfully go back and forth about this as if it was some sort of badge of honor. Accidents happen and rods do break from time to time, but I had guided one of these gentlemen and it was no secret why he had broken so many. When we first met, I cringed as he pulled his rod from the trunk of his car. It was not in a tube and there were a variety of items piled on top of it. I’ve seen a lot of rods break over the years, but I’ve never seen a single one break while it was in the tube. If you knew him, it would come as no surprise that he forgot to bring a reel for the rod, so he ended up using one of mine.

When we first met, I cringed as he pulled his rod from the trunk of his car. It was not in a tube and there were a variety of items piled on top of it. I’ve seen a lot of rods break over the years, but I’ve never seen a single one break while it was in the tube. If you knew him, it would come as no surprise that he forgot to bring a reel for the rod, so he ended up using one of mine.

Treating your breathable waders with a DWR is a great winter project. As a matter of fact, if you have a breathable rain jacket, grab it and treat it at the same time. DWR (Durable Water Repellant) is basically going to allow the water to “bead” and roll off the fabric rather than absorb into it. I’ve had old waders and jackets that I never treated that, even though they were still waterproof, were absorbing so much water that they felt heavy and even clammy. DWR is good stuff. There are a few brands out there and can usually be found at camping/outdoor stores. I’ve personally had good luck with ReviveX Spray-on Repellant.

Treating your breathable waders with a DWR is a great winter project. As a matter of fact, if you have a breathable rain jacket, grab it and treat it at the same time. DWR (Durable Water Repellant) is basically going to allow the water to “bead” and roll off the fabric rather than absorb into it. I’ve had old waders and jackets that I never treated that, even though they were still waterproof, were absorbing so much water that they felt heavy and even clammy. DWR is good stuff. There are a few brands out there and can usually be found at camping/outdoor stores. I’ve personally had good luck with ReviveX Spray-on Repellant. Start by washing the waders and/or jacket with a mild detergent as described above. Hang the garment(s) and spray evenly and thoroughly with DWR while the garment is still wet. I usually apply a little heavier around seams and stress areas such as the knees and crotch area on waders. On jackets, I put a little more emphasis on the shoulder area. You can then simply allow it to air dry where it’s hanging or put it in the dryer on low/medium for about an hour.

Start by washing the waders and/or jacket with a mild detergent as described above. Hang the garment(s) and spray evenly and thoroughly with DWR while the garment is still wet. I usually apply a little heavier around seams and stress areas such as the knees and crotch area on waders. On jackets, I put a little more emphasis on the shoulder area. You can then simply allow it to air dry where it’s hanging or put it in the dryer on low/medium for about an hour.

Hard Toothpick Indicators: These are usually made of cork, or balsa, or something similar. They are typically round or oval with a hole drilled in the center. The leader/tippet is inserted through the hole and the indicator may be moved to any position on the leader. Once the desired position is determined, the provided “toothpick” is inserted into the hole to hold the indicator in place.

Hard Toothpick Indicators: These are usually made of cork, or balsa, or something similar. They are typically round or oval with a hole drilled in the center. The leader/tippet is inserted through the hole and the indicator may be moved to any position on the leader. Once the desired position is determined, the provided “toothpick” is inserted into the hole to hold the indicator in place. Hard Rubber Band Indicators: These are typically oval in shape and made from the same materials as the hard toothpick type indicators. Instead of having a hole and a toothpick, they have a slit that contains athick rubber band. The leader is inserted into the slit and the indicator is then rotated, allowing the rubber band to twist around the leader to hold the indicator in place.

Hard Rubber Band Indicators: These are typically oval in shape and made from the same materials as the hard toothpick type indicators. Instead of having a hole and a toothpick, they have a slit that contains athick rubber band. The leader is inserted into the slit and the indicator is then rotated, allowing the rubber band to twist around the leader to hold the indicator in place.

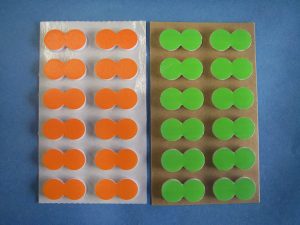

Stick-On Indicators: These are small round or oval pieces of foam that peel off and stick on to the leader. Their greatest value is that they cast easily, even when placed on the tippet and they make very little commotion on the water. So they are a great indicator for shallow nymphing. They float great and multiple indicators can be added to the line to support more weight.

Stick-On Indicators: These are small round or oval pieces of foam that peel off and stick on to the leader. Their greatest value is that they cast easily, even when placed on the tippet and they make very little commotion on the water. So they are a great indicator for shallow nymphing. They float great and multiple indicators can be added to the line to support more weight. Yarn Indicators: These are made from a buoyant yarn that is often pre-treated with a waterproofing agent, but floatant may also be added. There are a number of different versions of yarn indicators, but most attach by using some sort of slip knot or loop knot. Like the stick-ons, yarn can be attached to the tippet end of the leader without the worry of a hard landing or a lot of tangles. So this is another good choice for shallow nymphing. Yarn indicators are also very sensitive, so they are great for detecting subtle strikes.

Yarn Indicators: These are made from a buoyant yarn that is often pre-treated with a waterproofing agent, but floatant may also be added. There are a number of different versions of yarn indicators, but most attach by using some sort of slip knot or loop knot. Like the stick-ons, yarn can be attached to the tippet end of the leader without the worry of a hard landing or a lot of tangles. So this is another good choice for shallow nymphing. Yarn indicators are also very sensitive, so they are great for detecting subtle strikes. Putty Indicators: Strike putty comes in a small tub and resembles Play-Doh. You pull out a small gob or big gob depending on how big you want your indicator to be, and you smoosh and roll it on your leader. One of the benefits it that you can smoosh more on if you need more flotation for bigger, heavier flies, or you can pick some off for smaller flies and spookier fish.

Putty Indicators: Strike putty comes in a small tub and resembles Play-Doh. You pull out a small gob or big gob depending on how big you want your indicator to be, and you smoosh and roll it on your leader. One of the benefits it that you can smoosh more on if you need more flotation for bigger, heavier flies, or you can pick some off for smaller flies and spookier fish. Dry Fly: In the right situations, a dry fly can serve as an edible strike indicator by adding a nymph “dropper” to it. For many, this is the go-to method because you’re essentially doubling your chances… or so it might seem. Just like any other strike indicator, a dry fly has its pros and cons.

Dry Fly: In the right situations, a dry fly can serve as an edible strike indicator by adding a nymph “dropper” to it. For many, this is the go-to method because you’re essentially doubling your chances… or so it might seem. Just like any other strike indicator, a dry fly has its pros and cons.

As with most any fly fishing product these days, there are seemingly endless nipper styles and features to suit your needs and tastes. Some are just shaped differently, boasting a better ergonomic design. Others are equipped with additional tools for tasks such as tying knots or sharpening hooks. And if you want to take it to the next level, check out this description of Abel’s nippers:

As with most any fly fishing product these days, there are seemingly endless nipper styles and features to suit your needs and tastes. Some are just shaped differently, boasting a better ergonomic design. Others are equipped with additional tools for tasks such as tying knots or sharpening hooks. And if you want to take it to the next level, check out this description of Abel’s nippers: And they can be yours in black for a mere $85. For custom colors, they’re just $105. And with a cool fish print… a steal at $165. Yep, $165 for line cutters. All of a sudden, $10 for a pair of nippers doesn’t sound too bad, does it? As with anything else, if you have the disposable income and want to spend $165 of it on nippers, go ahead. I won’t judge you.

And they can be yours in black for a mere $85. For custom colors, they’re just $105. And with a cool fish print… a steal at $165. Yep, $165 for line cutters. All of a sudden, $10 for a pair of nippers doesn’t sound too bad, does it? As with anything else, if you have the disposable income and want to spend $165 of it on nippers, go ahead. I won’t judge you.