(It should be noted that this was written several years ago. I’m now have 50 firmly in my sights!)

I’ve been guiding fly fishermen for 20 years now and through those years, most of the fishermen I guided were men who were older than I was. I was reminded of this regularly as they would all routinely sit back observing as I tied on a fly, replaced a piece of 6x tippet, or cleared a tangle and calmly remark, “Wait til you turn 40.”

More focused on the task at hand than the comment, I’d reply, “How’s that?”

“Just enjoy your eyesight while you have it. It’s all downhill after 40!” And the two gentlemen would nod and laugh in mutual understanding and satisfaction that I would one day suffer their same misfortune.

If I heard it once, I heard it a thousand times, and it was never 38, never 42, never 45…. “Wait til you turn 40.” In my 20’s, the prophecy went in one ear and out the other. In my 30’s, I started to give it a little more pause, but still shrugged it off with what little was left of my youthful defiance. Last year I turned 40 and I’ll be damned if a week later I wasn’t holding the fly 6” further away to thread the tippet through the eye of the hook!

Now I find myself frequently guiding fishermen my age or younger and I take great pleasure in forwarding this curse to my clients in their 20’s. I even started sharing my story with older clients, thinking I was now part of some exclusive club. But no, they just smile, shake their head, and chuckle, “Wait til you turn 50.”

When I turned 40, it didn’t bother me a bit and I didn’t have any Earth shattering changes to my psyche or my general outlook on life. There was no desire to change careers, to buy a sports car, or to date a 20 year old swimsuit model. Maybe that comes at 50. But that society defined milestone does have a way of promoting self-reflection and I can honestly say I’m very content with where my life is right now. If I have one regret, it’s how my attitude and approach toward personal fishing trips has changed.

Whether it is born of laziness or wisdom, it has changed and it often leaves me disappointed in myself. I used to fish whenever I could, wherever I could, and for as long as I could – usually longer than I should. If there was an open day or an open slot in a day, I would somehow manage to fill it with fishing. It was not uncommon for me to drive three hours to fish for half a day and turn around and drive three hours back home. Or sometimes I’d turn that same trip into a two day event where I would spend the night in the back of my Explorer. Now I find myself reluctant to drive an hour and a half to fish the South Holston, regardless of how good the fishing will be, because I can be on Little River in thirty minutes. And if I do decide to spend the night on a fishing trip these days, it involves an elaborate camp or just as often, a hotel room.

I used to regularly explore new rivers and streams all over the region and now complacently opt for the more familiar waters that I’ve already fished hundreds of times. As a younger man I wanted adventure and discovery while as an aging man I tend to be leaning more toward stability and predictability. I also find myself leaning more toward quiet and solitude. Rather than driving two hours to a popular, crowded river where I’m likely to hook 20” rainbows on bead heads, I find myself hiking two hours to a small creek with nobody on it where I might catch 8” rainbows on dry flies.

My days on the water are now chosen more carefully, too. When I lived in Lexington, my longtime fishing buddy, Cecil, and I knew when each other was free and it was just understood that we would be fishing on those days, rain or shine, come hell or high water – we fished a lot of high water. After we got a little older and I moved to Tennessee, planning a trip became slightly more complicated as we would actually have to call each other a few times to determine an open date, and then we would go fishing, rain or shine, come hell or high water. Now going fishing with Cecil involves several e-mails and phone calls, a lengthy exchange of possible open dates, and an in-depth study of the Weather Channel. When we do finally settle on a date, it is still subject to change due to an alteration in work load, unrealized plans of spouses, or the weather.

Funny how things change. About 15 years ago, I took a winter trip to the Cumberland River with Cecil and another friend when the projected high was 25 degrees. It wasn’t a surprise or poor planning. We knew the high would be 25 degrees and we went anyway. It was an open day, the water releases were good, and we were fishermen. So we went fishing.

We had a beat-up johnboat and none of us had garages at the time so it was stored outside and usually uncovered. After all, funds were limited and you could buy a lot of fly tying materials for the price of a decent tarp. A winter’s worth of rain and snow had left the boat filled with water that had frozen to a solid block of ice by the time of our fishing trip, but not allowing such a minor detail to hinder a day of fishing, we decided to go ahead anyway and we’d figure something out when we got there. I think we secretly hoped that the ice would magically melt away on the two hour drive to the river, but to no real surprise, the exposure to 20 degree temperatures while driving 55 miles per hour only seemed to make the ice icier.

Once at the boat ramp, after repeated failed attempts to break the ice, things were looking grim, but with desperate times calling for desperate measures, I finally had the controversial idea of removing the drain plug and backing the boat into the river, allowing the near 50 degree Cumberland River water to fill the bottom interior of the boat to help melt the ice. Though it took several attempts, it actually worked and we eventually cleared the ice from the boat and made our way down the river. The fishing turned out to be excellent and Cecil stuck a 28” brown trout that day. These days, even with nicer boats stored in toasty garages, we probably would have opted to just stay home, maybe get a little work done.

That’s the most discouraging transformation that has occurred in my older age – the willingness to just stay home. I now find myself frequently choosing to tackle built-up yard work on a pleasant afternoon rather than slipping into the mountains with fly rod in hand. Maybe it has something to do with age, but more specifically, it is probably more the result of a misguided sense of responsibility that comes with age. I blame my father. After all, what kind of a writer would I be if I didn’t blame my father for at least one imperfection in my life? But when I was growing up, Dad rarely took vacations, and when he wasn’t working at the office, he was usually tending to some task at home, and I somehow managed to inherit this overwhelming sense of anxiety when projects begin to pile up, regardless of their significance.

I’ve begun to realize though, that I also have a responsibility to feed and foster the things that I’m passionate about. When I put off fishing trip after fishing trip, I do nothing more than build up an eventual feeling of desperation. Though I am fortunate to have a wife that supports my fishing addiction and even enjoys going with me, she inevitably becomes the undeserving target of the frustration brought on by too little fishing. In these instances, she might innocently ask what we’re doing this weekend, to which I respond sharply that I have to go fishing. I explain with irritation that I haven’t been fishing in weeks in a way that suggests that she’s the reason.

I’ll also find myself unproductive while working. Yes, I know the common perception of fly fishing guides is that we fish for a living, but while I’m fortunate that my job allows me to be on the water almost daily, being on the water and fishing are two completely things. Besides, there’s more to guiding than guiding. There’s the booking, the marketing, the fly tying, the boat maintenance, the grocery shopping, and the lunch making. For me, there’s also fly tying for the shop and writing. So when I’m trying to meet a deadline and I haven’t been fishing in a while, my mind will be all over the place and I’ll become extremely fidgety. This usually results in an indicting e-mail to Cecil about how we’ve become soft and how he needs to get his sorry ass down here and go fishing with me.

The fact is fly fishing is not just something I do. It’s a significant part of who I am. And when I go long stretches without fishing, it negatively affects me psychologically and becomes a detriment to the way I live the rest of my life. I don’t know if this is normal or not, but surely there must be others – fishermen, musicians, artists – who experience the same thing.

So I’m trying to do something about it. I’m trying to make myself fish more. Sad, isn’t it? What’s even sadder is when I feel the need to justify it by telling myself that I’m in the fly fishing business, so I need to fish. Or I play the mental health angle described above, convincing myself that I’ll be dead at 50 if I don’t spend more time on the water. Sometimes I even envision the tombstone:

Here’s lies Rob Fightmaster. He died forty years too soon because he didn’t fish enough.

I shouldn’t have to do that though. I should be able to go fishing for no other reason than I’m a fisherman and I want to go fishing, right? It’s unfortunate that things like work so often interfere with the important things in life. Responsibility comes in many forms and we can’t lose sight of the fact that we are ultimately responsible for our own happiness and contentment. And when we are happy and content, we are able to share a better part of ourselves with the people that matter most.

So, sorry Little River Outfitters. That bin of Hellbender Stoneflies will have to stay empty a couple of days longer. I’ve blocked a day to go fishing this week! Well, as long as it doesn’t rain….

Summer is creeping slowly into the Smokies and fly patterns are beginning to shift again. In late spring and summer, nearly everything that hatches is brighter in color. Most of the aquatic insects you see are some shade of yellow or bright green, so it certainly makes sense to fish fly patterns in the same color profile.

Summer is creeping slowly into the Smokies and fly patterns are beginning to shift again. In late spring and summer, nearly everything that hatches is brighter in color. Most of the aquatic insects you see are some shade of yellow or bright green, so it certainly makes sense to fish fly patterns in the same color profile.

In June, hatches start to thin out. We still see a fair number of Yellow Sallies and a smattering of caddis and mayflies, but the heavier, attention getting hatches of spring have mostly come to an end. But when summer eases its way into the mountains, trout turn their attention to terrestrials, and so should you. We’ll talk about several varieties of terrestrials over the coming months but we’ll start with the granddaddy of all mountain terrestrials: the Green Weenie.

In June, hatches start to thin out. We still see a fair number of Yellow Sallies and a smattering of caddis and mayflies, but the heavier, attention getting hatches of spring have mostly come to an end. But when summer eases its way into the mountains, trout turn their attention to terrestrials, and so should you. We’ll talk about several varieties of terrestrials over the coming months but we’ll start with the granddaddy of all mountain terrestrials: the Green Weenie.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.

The Ginger Caddis of the Smokies is known in other circles as the Great Brown Autumn Sedge. Many lump it together with a few other similar species and refer to them all just as October Caddis. No matter what we decide to call it, fish just call it food! Caddis of numerous varieties are available most of the year in the Smokies but really seem to come into their own in fall. And of the many caddis species hatching in the fall, the Ginger Caddis is the undisputed king.

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

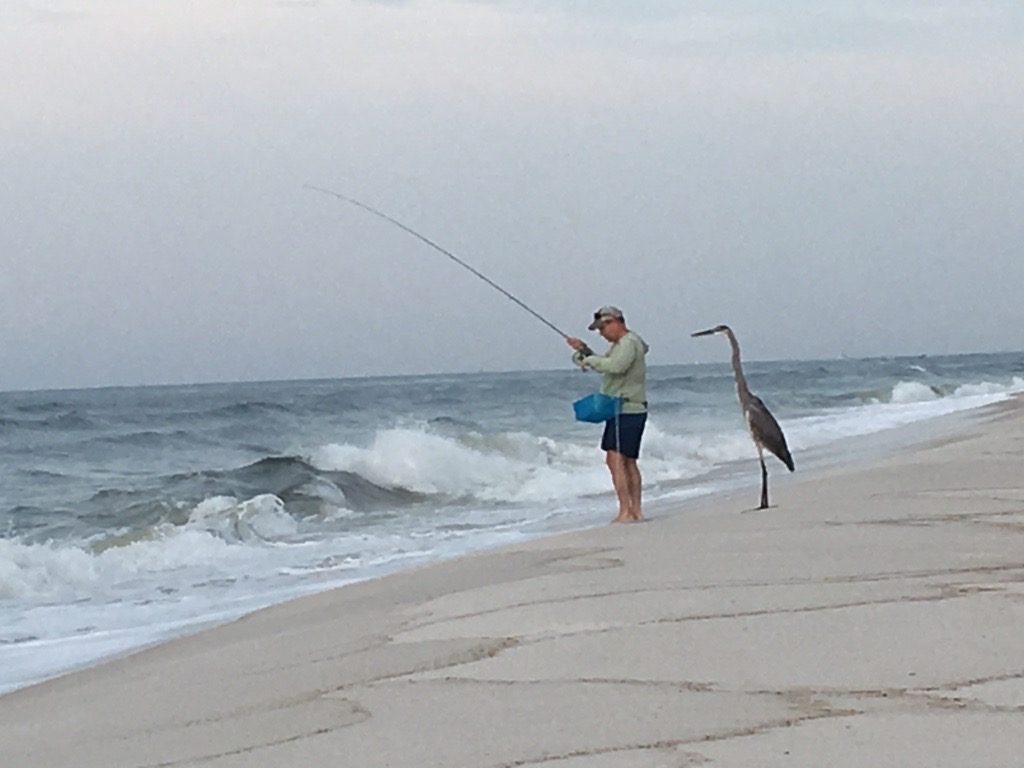

Every time I go to the beach on vacation, I take a fly rod with me. Sometimes I already have plans to do some flats fishing with a guide but just as often, my only plan is to get up early each morning and cast around in the surf to see what might bite. That’s one of the neat things about fishing in the ocean. You never know just what you might find!

Every time I go to the beach on vacation, I take a fly rod with me. Sometimes I already have plans to do some flats fishing with a guide but just as often, my only plan is to get up early each morning and cast around in the surf to see what might bite. That’s one of the neat things about fishing in the ocean. You never know just what you might find!

These are hardly the idealized fly fishing journeys that most anglers conjure in their minds in those last few moments before sleep takes hold. It’s not the casual, early morning stroll through a dewy meadow to the spacious pool in a lazily meandering river where 20-inch trout routinely clock in for their daily shift of methodically sipping delicate mayflies. In fact, unless you are one of a few passionate, dedicated, and perhaps slightly mentally unbalanced backcountry anglers, you might consider these journeys way too much like work.

These are hardly the idealized fly fishing journeys that most anglers conjure in their minds in those last few moments before sleep takes hold. It’s not the casual, early morning stroll through a dewy meadow to the spacious pool in a lazily meandering river where 20-inch trout routinely clock in for their daily shift of methodically sipping delicate mayflies. In fact, unless you are one of a few passionate, dedicated, and perhaps slightly mentally unbalanced backcountry anglers, you might consider these journeys way too much like work.