Over the years, one of the most frequent questions I’ve been asked is about the trout in the Smokies. What kind are there? Where did they come from? How big do they get? Why don’t they get bigger? Why don’t they stock fish in the park? The list goes on and on. I thought I’d take this opportunity to satisfy some of the curiosity of enquiring minds.

Trout fishing in the Smokies starts with brook trout. They are the native fish of the Smoky Mountains. The terms native and wild are often confused and misused when referring to fish. To clarify, a wild trout is a trout that is not stocked but was born in the stream. However, it may have been introduced through stocking at one time. All trout in the Smokies are wild – there has been no stocking since the early 1970’s. A native trout is one that has always been there and was not introduced by humans. Brook trout have been in the Smokies since the last ice age!

It used to be that every stream in the Smokies had brook trout and rainbows and brown trout were non-existent. The intense logging of the area, prior to its designation as a national park, sparked that change. In the early 1900’s, logging practices simply weren’t very responsible and they cut any and every tree they could get to. When trees near mountain streams were removed, critical canopy to provide shade on these waters disappeared and water temperatures climbed to levels in the warmer months that made them uninhabitable for coldwater species like brook trout. Many of the brook trout migrated to high elevations for cooler water. The ones that didn’t died.

Over time, logging operations came to a stop – in some places because there was nothing left to cut, and in others because the national park was formed and the land was protected. In the former, many streams were stocked with trout (mainly rainbow) to appease some of the emerging sporting clubs and camps. Brown trout were also introduced in a handful of rivers. Even after the formation of the park, the National Park Service continued to stock these rivers with trout.

By the time the forest regrew to a level of maturity and much needed canopy returned to cool low and mid elevation streams, the rainbows and browns had established a foothold, and the native brook trout could not compete for the limited food source, forcing their relegation to the high country.

This changed again in the early 1970’s when the NPS began using electroshocking techniques to sample streams for data on fish population and size. Prior to that, they had to rely solely on creel surveys – asking fishermen how many they caught and what size. Well, as you hopefully know, just because you’re not catching fish or seeing fish doesn’t mean there are no fish! The electroshocking proved that, and they learned that they were stocking fish on top of fish. The rainbow and brown trout were all reproducing, and had been for some time.

They ceased the stocking of streams at that time and they have been thriving as wild trout fisheries ever since, boasting park-wide populations of anywhere from 2000 to 6000 fish per square mile. The only two things that seem to make that number fluctuate are flood and drought. They have determined that fishermen have absolutely no impact on the fish numbers. In fact, fisheries biologists agree that it could very well be a healthier fishery, at least when it comes to fish size, if more fishermen kept fish to keep the numbers down.

Brook trout and rainbow trout in the park only live about 4-5 years. Brook trout rarely exceed 10” in size and rainbows rarely exceed 15”. There are no regulations, like catch-and-release or slot limits, that can change this. These mountains are some of the oldest in the world and consequently are more acidic. Streams with low ph levels have less aquatic insect life, which is the primary food source for rainbow and brook trout.

So we simply have too many fish for the available food source. Years with heavy flooding or intense drought often kill a generation of fish, reducing the population significantly. In the year or two following such an event, even though the fish population might be decreased by a third, fishermen still catch the same number of fish they always did, but the fish they do catch average 1-2” bigger. More food for fewer fish equals bigger fish.

Brown trout in the Smokies seem to be the exception to all of this. While they are only in a limited number of streams, they can live 15 years and reach lengths of 30”! Biologists believe one of the main reasons for this is their tendency to add bigger fare to their diet. Rainbows and brookies pretty much stay bug eaters in the park. While brown trout also eat bugs, when they reach a size of 8 or 9”, they also begin eating crayfish, mice, leeches, and smaller fish – including smaller trout!

Brown trout like low light, do a lot of their feeding at night, and are just generally reclusive. So they don’t get caught very often. You simply don’t go to the Smokies expecting to catch 20” brown trout on every trip. But in the right rivers, it’s always a possibility. In general, if you catch a trout in the Smokies bigger than 7” you’ve caught a pretty good fish. If your goal is purely to catch big trout, go to a tailwater, the Smokies isn’t for you.

Tailwaters are rivers created by water release from a dam and there are several in East Tennessee. They are stocked regularly by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Most of the trout they stock in these rivers are 7” or bigger and grow quickly thanks to the ample food supply found in these fertile waters.

When it comes to fish size, the bottom line is it’s relative to where you are fishing. A 12” native brook trout in the Smokies is a rare thing and surely qualifies as a “trophy.” A 12” stocked rainbow in the Clinch River is a dime a dozen.

The arrival of November usually means cold weather is not too far off, but it doesn’t mean that you have to quit fishing. Certainly the fishing for wild, mountain trout can slow down significantly as water temperatures fall, but tailwater trout and really any stocked trout will continue to feed well, even in the coldest of temperatures. In recent years, winter guide trips to Delayed Harvest streams have become a favorite of many clients, mainly because of the potential for really big trout.

The arrival of November usually means cold weather is not too far off, but it doesn’t mean that you have to quit fishing. Certainly the fishing for wild, mountain trout can slow down significantly as water temperatures fall, but tailwater trout and really any stocked trout will continue to feed well, even in the coldest of temperatures. In recent years, winter guide trips to Delayed Harvest streams have become a favorite of many clients, mainly because of the potential for really big trout.

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s.

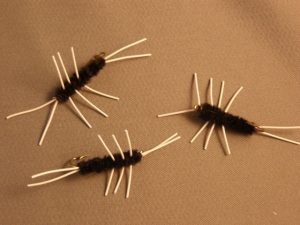

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s. Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.”

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.” Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall.

Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall. Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way. the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason.

the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason. March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year.

March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year. Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.

Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

In general, I mostly look forward to spring and fall fishing the most in the mountains. Temperatures are mild and fish are typically at their most active. However, there is one particular thing that makes me excited for the warm weather of summer to arrive: Beetle fishing!

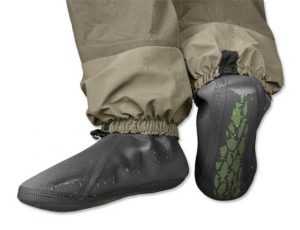

October is the time of year I start wearing waders again in the mountains. For much of the year, usually from May through October, water temperatures are comfortable enough to wet wade, wearing only the wading boots and neoprene socks. But in winter, early spring, and late fall (or any time of year on tailwaters), you better have a decent set of waders if you want to stay comfortable on the stream.

October is the time of year I start wearing waders again in the mountains. For much of the year, usually from May through October, water temperatures are comfortable enough to wet wade, wearing only the wading boots and neoprene socks. But in winter, early spring, and late fall (or any time of year on tailwaters), you better have a decent set of waders if you want to stay comfortable on the stream.