In April, dry fly fishing really starts to turn on in the Smokies. Not only are there a significant number of hatches, but water temperatures are getting ideal and fish are just looking up, even when no hatches are present. Presenting a dry fly that rides high on the water, not only tends to produce more strikes, it is much easier for you to see. Here are a few tips to keep your fly floating high in the fast moving currents of the Smoky Mountains.

First off, if you don’t tie your own flies, be sure buy high quality dry flies. It can be tempting to find Internet companies or box stores that offer really cheap prices on flies, but they are cheap for a reason. These dry flies often have less hackle and/or use a very low-grade hackle, and they are simply not going to float as well. Bushy, heavily hackled flies will float the best, as will flies that utilize foam and/or deer hair. These are all great for most of the riffles and pocket water you encounter in the Smokies. However, if you’re fishing to slow water risers in a slick pool, you may want to use a more slender, low profile fly like a parachute or comparadun pattern.

Treat your flies before you fish them. There are a number of great products on the market that accomplish this and are generically referred to as fly floatant. The most common are silicone based and have a gel consistency. Just squeeze a drop on your finger and rub it into your fly. Orvis, Aquel, Loon and Gink are probably the most common brands. They’re all probably about the same but everyone seems to have their favorite. I use Orvis Hy-Flote.

Once you’ve selected your high quality dry fly and gooped it up with fly floatant, the worst thing you can do to it is catch a fish! They take it under water and slime it up to the point where it doesn’t want to float as well, especially after you catch 2 or 3 fish. When this happens, a mistake a lot of anglers make is to re-apply the same gel floatant they used to pre-treat the fly. However, you’re often just trapping moisture in to the fly at this point. You need to remove as much of the moisture from the fly as possible.

On bigger rivers such as tailwaters, your false cast can keep a lot of moisture out of the fly, even after several fish. But in places like the Smokies, frequent false casting is often not an option due to the tighter quarters, and is often not desired because of the increased risk of spooking fish. There are a number of methods I use to dry a saturated fly in these environments.

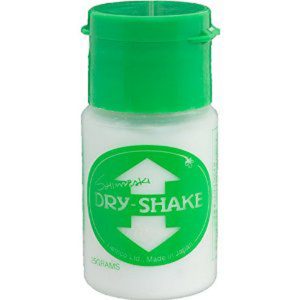

One is to press the fly against an absorbent material. Amadou is a material sold at many fly shops that works great for this. You can carry a patch on your vest or pack and just squeeze the fly in it. Chamois cloth is another good option. If you’re in a pinch and don’t have either, just press the fly against your shirt. After employing this method, blow on your fly. Finally, consider carrying a second, powder based floatation product. These are desiccants, similar to what’s found in the small, “do not eat” pouches packaged with some clothing and electronics. Again, there are numerous brands. Frog’s Fanny is a favorite of many anglers. My favorite is Shimazaki Dry-Shake. It has a large-mouthed bottle that allows you to drop the fly in while still attached to the tippet. Close the lid, shake vigorously and remove. It will be floating like new.

The final tip for keeping that fly floating high is technique. What causes flies to get waterlogged more than anything else, especially with novice anglers, is drag. When your fly doesn’t drift naturally with the current, and instead pulls unnaturally against the current, not only will you not catch many fish, your fly is going to become more waterlogged and require far more maintenance to keep it floating.

Think about what you’re doing. Instead of dragging the fly through the run 2 or 3 times before making a good drift, read the water. Identify the varied currents that will pull your line at a different speed than the fly and try to position yourself where you can eliminate them. If you can’t eliminate them through position, think about how, when, and which direction you’ll need to mend BEFORE you make the first cast. And pick your fly up when it reaches the end of the target area, rather than letting it drift (drag) into the fast shallow riffle at the bottom of the run.

Experienced anglers often do most of this instinctively, so it looks like they’re just casually moving around casting. The good ones always make it looks easy! If you’re newer to fly fishing or even if you’ve done it awhile but only get out a few times a year, it won’t be instinctive and you’ll have to think about it. This is just good advice, period. If you execute a good cast and drift in the right place the first time, you’ll not only keep your fly floating better, you’ll catch more fish!

Finally, on a similar note, carry your fly in your hand when you move from spot to spot. I see a lot of people who will let their fly drag behind them in the water as they wade up to the next pocket or run. If you do this, the best-case scenario is that you’re going to waterlog your dry fly. More often than not, you’re also going to hang your fly up on every rock and stick in the river!

The arrival of November usually means cold weather is not too far off, but it doesn’t mean that you have to quit fishing. Certainly the fishing for wild, mountain trout can slow down significantly as water temperatures fall, but tailwater trout and really any stocked trout will continue to feed well, even in the coldest of temperatures. In recent years, winter guide trips to Delayed Harvest streams have become a favorite of many clients, mainly because of the potential for really big trout.

The arrival of November usually means cold weather is not too far off, but it doesn’t mean that you have to quit fishing. Certainly the fishing for wild, mountain trout can slow down significantly as water temperatures fall, but tailwater trout and really any stocked trout will continue to feed well, even in the coldest of temperatures. In recent years, winter guide trips to Delayed Harvest streams have become a favorite of many clients, mainly because of the potential for really big trout.

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s.

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s. Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.”

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.” Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall.

Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall. Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way. the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason.

the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason. No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves.

No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves.

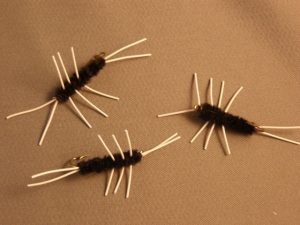

Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

As about anyone who knows me can tell you, I’m terrible at self-promotion. The worst. So it should come as no surprise that I’ve never featured one of my own patterns in the newsletter. Usually I opt for more standard or classic patterns. But this is a good fly and it’s good this time of the year, so here you go!

As about anyone who knows me can tell you, I’m terrible at self-promotion. The worst. So it should come as no surprise that I’ve never featured one of my own patterns in the newsletter. Usually I opt for more standard or classic patterns. But this is a good fly and it’s good this time of the year, so here you go!