“While the snow whorled, the old men would work at the desk with the glow of bemused gods, forsaking reason and good sense in their search for the great concoction, the random mating of fur and feather and colored thread that would break new ground in piscatorial seduction, speak in the language of pure appeal, fascination, enticement, allure, the perfect corruption, hooked bribe, deadly enchantment, a come-on no fish could deny, something beyond mere interest, something exotic and irresistible. No combination was too distasteful or out of bounds, no creation too shocking.”

– Harry Middleton, Rivers of Memory

Tying flies just seems to be a natural progression for any avid fly angler, though it becomes more of an obsession for some than others. Some possess a romantic ideal of catching a fish on a fly that they’ve crafted with their own hands while others simply fish so much and burn through so many flies that they see fly tying as a means of stopping the bleeding, a practical means of saving money. Many more enter the world of fly tying with delusions of grandeur, possessing an unbridled optimism and certainty that they will be able to catch more or better fish by filling a void with a creation not yet imagined by the world’s tying minds and not yet available through their local shop’s selection. That 29” brown trout under the bridge is just a bead-head-bright-green-bodied-pink-tailed-red-rubber-legged nymph away from being caught! I began with similar delusions and like most tyers, still have them. Somewhere deep in the creative recesses of my mind, I surely hold the key to the ultimate creation: The dry fly that won’t sink, the nymph that won’t hang the bottom, the streamer with just the right “waggle”…. All tied in such a unique, unprecedented way that trout will come from neighboring pools just to get a taste…. The perfect fly.

However, the budding fly tyer is quickly faced with the reality that there is an art to this fly tying thing and that an unspeakable number of very imperfect flies will be born at the vise before the perfect fly can ever emerge from the dubbing dust, especially when you begin the task as I did, with a shortage of funds and a surplus of stubbornness. Determined to teach myself rather than spend time and money taking a class, my first of many mistakes, my response to the overwhelming myriad of materials and tools confronting me was to purchase a starter kit. Fly tying kits aren’t a bad way to get started at all; especially when you have one personally assembled for you by someone at a fly shop who can get a feel for what flies you’re interested in tying. But I opted for the pre-selected, company kit that was assembled probably more as a means of ditching materials that wouldn’t sell than as something to ease my transition into the art of fly tying.

The kit regretfully came from one of the large catalog companies, cost $150, and was advertised as having everything I’d needed to start tying flies: vise, tools, hooks, materials, and a book to show me how to do it. To no real surprise, the materials were extremely low grade, with the provided colors apparently selected for patterns no longer in production. Or someone thought red and yellow were the two universal colors for everything from hackle and marabou to chenille and dubbing. The pocket sized book turned out to be equally disappointing with about twenty pages that included such detailed instructions as: Put hook in vise. Attach thread to hook. Tie feather to hook. Dub body. There were no technique pictures, no definitions, and really only about five illustrated patterns. So I tied a few mutant Wooly Buggers with massive, 10” yellow tails that included even the thick stem, red bodies that were plump at the hook bend and skinny near the head, red palmered hackles that ended about halfway up the body, and a thread head the size of a marble.

I also tried my luck with dry flies but due to limited materials, the fact that I really didn’t know what the materials were, and that I had no discernible skills, they didn’t quite turn out like the ones in the fly shop. They did look exactly like mayflies – assuming we’re talking about mayflies that have been smashed on your car windshield and spread a few times with the wiper blade. They consisted of 2” tails that pointed down because I tied them too far back on the hook. The body was a thick, lumpy mass of mangled fur because I didn’t know how to spread and twist dubbing on a thread. The hackle was big and soft since I was using broad saddle hackle from the kit. You mean there are different types of hackle? And to finish it off, the hook eye would be inaccessible, covered over in thread wraps since I never left enough room to wind a head. That actually may have been a cosmic favor – the universe suggesting that I might want to reconsider attaching this monstrosity to the end of my tippet.

I eventually put all the pieces together and twenty years later, I can say that my flies do catch fish, they look kind of pretty, and I’m finally to the point where I’m saving a little money. In fact, as a commercial tyer, I now even get to say I’m making money, but if I’m being honest, most of my profits go right back into materials to tie more flies – the circle of life. There are people that solely make a living tying flies but I’m not one of them. Other than offset some other expenses, all commercial fly tying has really done for me is significantly change my perspective on the value of a fly. It didn’t take long before I went from, “They want $2.00 for one fly?!” to “They only get $2.00 for a fly?!”

Making the jump from recreational fly tying to commercial fly tying also has a way of stifling any creative ambitions you once may have possessed as you become confined to a one person assembly line of feathers and fur, repetitively producing dozens of the exact same fly. I get hit from two sides as I try to keep many of the bins full at the local fly shop while still keeping my own boxes full for guide trips, constantly replenishing staple patterns routinely sacrificed to high tree limbs by eager fly fishing virgins. Still, that creative yearning never goes away and routinely creeps up and distracts me while I’m four dozen deep in a fly tying shift of redundancy. An hour later, I’ve aborted the task at hand and have tied six Parachute Adams with pink rubber legs, chartreuse hackle, and a spinner blade for a tail.

Okay, that may be a bit of an exaggeration, but I have, for whatever reason, had some really bad ideas for fly patterns. They were all born of what, at the time, seemed to be sound theory but in retrospect are pretty difficult to justify. Despite these failures in fly tying evolution, over the years I have created some flies that turned out to be very productive, but I don’t know how original any of them really are. The patterns I create most often tend to be variations of already established patterns, posing the question of what actually constitutes an original fly pattern.

Fly tying is much like cooking in that regard. Very rarely is a brand new recipe created anymore. Rather, traditional recipes are often tweaked to create a slightly different flavor or texture. If I cook ground beef and put it on a bun, it’s a hamburger. If I add cheese it’s a cheeseburger. If I add sautéed onions, it’s a cheeseburger with sautéed onions. But if I make the same thing on different bread it becomes a Patty Melt. If I use chartreuse grizzly hackle on a Parachute Adams and add pink rubber legs, is it simply a Chartreuse, Rubber-Legged Parachute Adams, or is that enough variation to be considered an original pattern warranting a clever new name?

What is it that even motivates so many fly tyers to attempt so many new patterns when the old standards seem to work just fine? Is it an attempt at something better or merely an attempt at something different? Is it for the fish’s benefit or our own? Maybe it’s because with a new fly pattern comes new hope. Success with a particular fly, whether it is an old standard or a new concoction of your own design, really just seems to boil down to personal confidence. When you have confidence in the fly with which you’re fishing, you naturally fish it harder and fish it better. It’s funny how that works. I know that the Muddler Minnow is a fantastic fly and that it works. It’s probably one of the top five freshwater streamers ever created but while I’ve been in the company of numerous fishermen who catch several fish and big fish on it, I couldn’t catch a fish on that fly if I cast it in a trout tank at the local boat show. It has just never worked for me and I suppose that’s because, for whatever reason, I just don’t fish it with confidence.

What I’ll really never understand are the flies that go in and out of “style” – not necessarily with fishermen, but with fish. Some flies have been staples for me since the day I started trout fishing while others seem to fall in and out of vogue. I used to tie and fish a fly called a Mallard Minnow that, back in the day, would catch any kind of fish in any kind of water. I thought about it once and realized that on that fly, I’d caught rainbow trout, brown trout, brook trout, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, rock bass, striped bass, bluegill, gar, carp, catfish, walleye, and salmon. It probably would have also accounted for saltwater fish if given the chance but at some point, it just quit working. It was a fly in which I once had total confidence and unmatched success and I haven’t had a fish so much as look at it since the late nineties.

Why is that? Are flies to fish what clothes are to us? Do they have fly shows every spring to feature the latest trends? Maybe that large brown trout behind the stump is rolling his eyes at my Mallard Minnow, telling his rainbow trout friend, “That is so 1995.” Are there also trout with retro tastes that are looking for fly patterns from the fifties and sixties? If so, I suppose that’s why a good old standard Wooly Bugger would top my list as the perfect fly. Like a basic pair of blue jeans, it seems to always be in style. But if it just had a propeller at the head….

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s.

We’ve talked a lot about water temperature in many of these articles and for good reason. Things like approach, presentation, and fly selection can determine whether or not a fish will take your offering, but water temperature can determine whether or not a fish will take any offering! You can read in more detail about water temperature in A Matter of Degrees, but to keep it simple here, wild trout in the Smokies just don’t do a lot of feeding when the water temperature is in the 30’s and low 40’s. Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

Once you think you’ve located feeding fish, it’s time to think about fly selection. On warmer winter days, you may actually see some insects hatching. If you do, they’re likely to be small and dark: Blue Wing Olive mayflies, small black stoneflies or caddis, dark olive or black midges… Rarely anything bigger than a #18. On rare occasions, you may see fish feeding on the surface during one of these hatches. Small Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnats are a pretty good bet in those instances. Mostly though, they’re going to feed more on the nymphs, so black Zebra Midges, small Pheasant Tails, and small black or olive Hare’s Ears will be pretty good bets.

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.”

It’s the time of year when certain folks seem to be whispering more at the fly shop. They’re isolated in corners and peeking over their shoulders before saying too much. They’re talking about brown trout. Big ones. Somebody mentioned seeing a decent one around Metcalf Bottoms – about 18-inches. A younger guy innocently asked, “Since when did we start referring to 18-inch browns as ‘decent’?” The older guy replied with a grin, “October.” Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall.

Fish that size don’t get caught often. Brown trout only live in a handful of rivers in the Smokies to begin with. They’re extremely cagey and for much of the year, they do most of their feeding at night – it’s illegal to fish the park at night. So, outside of the occasional big brown caught at dusk, or dawn, or after a good rain, we don’t get a lot of good shots at these guys. Until late fall. Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

Most people aren’t willing to put in the time it takes to catch one of these fish. Unless you’re just going to depend on luck, you have to trade fishing time for looking time. You may not spot one at the first place, or second or third… And once you do spot one, you’re not done looking. You have to watch him for a while to figure out his pattern: how he’s feeding, where he’s feeding, when he’s feeding, IF he’s feeding. You then may have to spend a pain-staking amount of time sneaking into a position where you can cast to him without spooking him.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way.

The best prevention for all of these, of course, is good old-fashion bug spray. Bug sprays with higher concentrations of Deet seem to be most effective, but be careful when using them. Deet has the ability to melt plastic, and getting a healthy dose of Deet heavy bug spray on your fingers can wreck a fly line. Just avoid spraying it on your palms and finger tips. If you’re one who likes to spray your hands and rub it on your face, just spray the back of your hands and rub it in that way. the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason.

the woods, there’s a chance of picking up a tick. Deet based bug sprays will help with that, too. I still try to check myself periodically, particularly at the end of the day. If you do find one on you, there’s an easy way to remove it. Squeeze a dab of medicated lip balm (the gel type that comes in the squeeze tube) onto your finger and smear it on the tick. It will immediately release itself from your skin. Cool, huh?!? I always keep a tube of Carmex in my first aid kit for this reason. No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves.

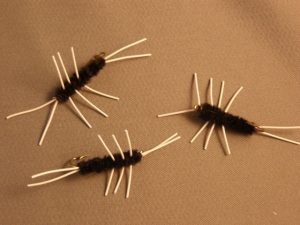

No fly holds near the lore among East Tennessee fly anglers as the Yallarhammer. It has long been known that the native brook trout that reside in Southern Appalachian mountain streams have a weakness for brightly colored flies, particularly if that bright color happens to be yellow. But before endless varieties of fly tying materials were so easily available from local fly shops, mail order catalogs, and the Internet, early fly tyers had to use feathers from local birds that they could shoot themselves. Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

Since we’re talking about big browns this month, I thought it only fitting to feature one of my favorite flies for big brown trout. While I have caught a number of big browns on small flies over the years, most of the big guys in the mountains have come on larger stonefly nymphs. This is a little bit misleading as most of the large browns I’ve caught in the Smokies I spotted before I fished for them. And when I spot a big brown trout, I almost always tie some sort of stonefly nymph imitation to my line. Who is to say I wouldn’t have caught those same fish on a #20 Zebra Midge had I chosen that fly?

As about anyone who knows me can tell you, I’m terrible at self-promotion. The worst. So it should come as no surprise that I’ve never featured one of my own patterns in the newsletter. Usually I opt for more standard or classic patterns. But this is a good fly and it’s good this time of the year, so here you go!

As about anyone who knows me can tell you, I’m terrible at self-promotion. The worst. So it should come as no surprise that I’ve never featured one of my own patterns in the newsletter. Usually I opt for more standard or classic patterns. But this is a good fly and it’s good this time of the year, so here you go!

Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.

Even with all the newfangled fly patterns and fly tying materials available today, I usually find myself sticking more with the old staples, or at least pretty similar variations. And I stick with them for one main reason: They work! Created by fly tying guru, Dave Whitlock in the 1960’s, this fly definitely falls under the “old staple” category.

March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year.

March is the month when trout fishing in the Smokies officially kicks off. Days are getting a little longer, temperatures are getting a little warmer and water temperatures are on the rise. It’s also the month when we begin to see our first good hatches of the year. Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.

Quill Gordons are fairly large mayflies, between a #14-10 hook size, that begin to hatch when the water temperature reaches 50-degrees for a significant part of the day, for a few days in a row. In unusually warm years, they’ve hatched as early as mid February. In particularly cool years, they may not hatch until April. But most years on the lower elevation streams in the Smokies, this occurs about the third week of March.